Description of previous item

Description of next item

April 1862: Carnage and Conscription

Published April 4, 2012 by Florida Memory

On the morning of April 6, 1862, the men of the 1st Florida Infantry Battalion crossed Shiloh Branch stream to engage the enemy in what turned out to be one of the bloodiest battles of the Civil War. In two days of fighting, over 23,000 men died in the Battle of Shiloh, which saw two massive Union and Confederate armies clash in the fields and woods surrounding Shiloh Meeting House, a Methodist Church near the banks of the Tennessee River in southwest Tennessee.

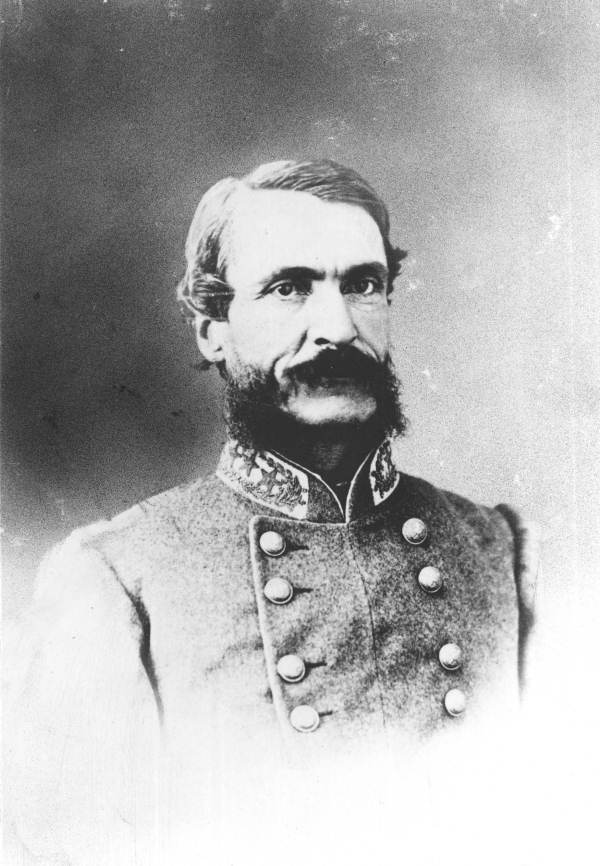

The 1st Florida Battalion was a unit in the brigade of Brigadier General James Patton Anderson, a part of General Albert Sydney Johnson’s Army of Mississippi. Anderson, a member of Florida’s secession convention and delegate to the Provisional Confederate Congress in Montgomery, had commanded Florida troops at Pensacola before being ordered to move his men to Corinth Mississippi to reinforce the faltering Confederate front in the west.

At Shiloh, Patton’s Floridians became the first Florida soldiers to see action outside of their state. In one of the most terrifying engagements of a battle that was full of horrible episodes, the Floridians were among the Confederate forces that charged the Union troops defending the Sunken Road. After only a few minutes of fighting, the Florida Battalion lost several officers and men but continued to attack the Union position. The battalion survived to fight on April 7, the second day of the battle, and ended the fight with over a quarter of its strength of 250 men either dead or wounded. Although the Union army under Major General Ulysses S. Grant lost more men than the Confederates, the Confederates failed in their mission of destroying Grant’s army and withdrew back into Mississippi.

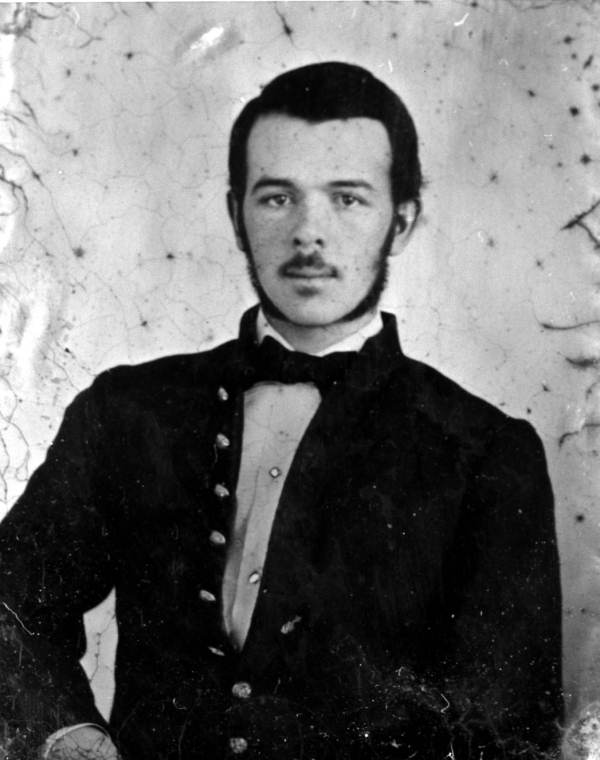

Confederate soldier Lawrence “Laurie” M. Anderson of Tallahassee, killed at the Battle of Shiloh on April 7, 1862

The carnage at Shiloh—the Confederates suffered over 10,000 casualties—combined with the toll of the battles waged across the South since secession resulted in the Confederate government’s decision to pass the Conscription Act on April 16, 1862. The Conscript Act, as it was usually called in the press of the day, was the first national draft in American history (the Union would begin drafting men in 1863). Although President Jefferson Davis and a majority of the Confederate Congress supported the act, conscription was probably the most divisive and unpopular Confederate law passed during the war. The Conscript Act authorized the Confederate president to draft all able bodied white male residents of the Confederate States between the ages of 18 and 35 for three years of military service and extended the service of all men of draft age already in the Confederate forces.

In order to avoid the stigma attached to conscription, which many Southern men saw as an affront to their honor because it seemed to question their willingness to fight, most men volunteered before the draft took effect. Men and women across the South also hated the Act because it allowed a man who could afford it to pay a substitute to serve in his place. Politically, the draft was unpopular because it seemed a direct threat to states’ rights, the doctrine that the South had used to justify secession. Up to 1862, only states could draft men (usually for emergency militia service). Now the national government was demanding that states turn over their men for military service rather than allowing states to organize volunteers and offer them for service as had been done in all of America’s previous wars.

Many state governors denounced the Conscript Act as unconstitutional and resisted compliance. This was especially the case for Florida’s neighbor Georgia, where Governor Joseph E. Brown became the South’s principal opponent of the draft and the policies of Jefferson Davis. Brown made every effort to resist and delay the implementation of conscription in Georgia.

In Florida, Governor John Milton was also philosophically opposed to the draft as an infringement on states’ rights; however, he was willing to put off the question of the constitutionality of the draft until after the war was won. Milton reasoned that the constitutionality of the Conscript Act would be irrelevant if the South lost the war. He believed it was more important for the states to support President Davis and the Confederate government to enroll the manpower necessary to fight the Union: “Impending clouds of destruction hover over, and threaten the destruction of our liberties, of all rights of property, and the dishonor of our wives and children. The threatened evils can only be prevented by concert of action between the State Governments and the Confederate Government, and the indomitable and invincible courage and unfaltering patriotism of our entire population.”

Milton never retreated from these words contained in his 1862 annual message to the state legislature. He became one of the staunchest defenders of conscription and the leadership of Jefferson Davis, even naming a son born in 1863 after the Confederate president. This son, Jefferson Davis Milton or “Jeff Davis,” became one of the West’s most famous law enforcement officers, serving the U.S. government as a legendary immigration officer along the Mexican border, defending the sovereignty of the nation his father had tried to defeat.

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "April 1862: Carnage and Conscription." Floridiana, 2012. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/252643.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "April 1862: Carnage and Conscription." Floridiana, 2012, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/252643. Accessed December 29, 2024.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2012, April 4). April 1862: Carnage and Conscription. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/252643

Listen: The Gospel Program

Listen: The Gospel Program