Description of previous item

Description of next item

Needs More Salt

Published July 7, 2012 by Florida Memory

The Union naval blockade of the South severely limited the Confederacy's overseas trade. While swift moving blockade runners managed to evade Union warships throughout the war, these vessels could not possibly bring in enough goods to make up for the loss of trade. This loss was especially glaring for one crucial commodity: salt.

Although there were large salt mines in Virginia, cheap foreign-produced salt had been the South's major source of the mineral before the war. Within months of the war's outbreak, the Confederacy faced a salt crisis as its armies, which required massive supplies of salted pork, and citizens quickly used up stocks of the vital preservative. The South soon turned to Florida to make up its sodium deficit.

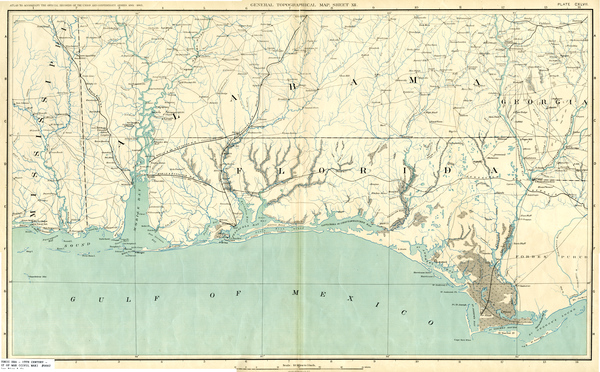

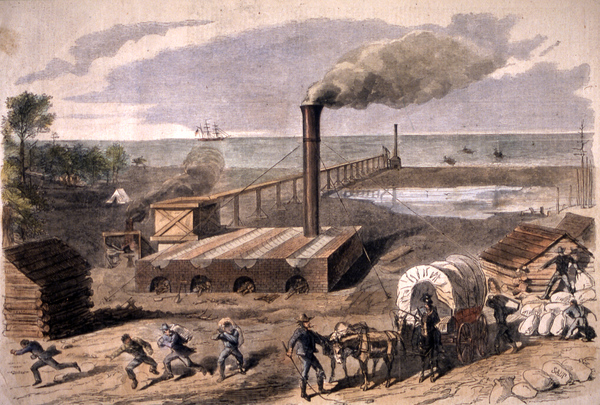

Florida's long coastline made it ideal for salt production. The process involved boiling kettles of seawater and refining the salt though a process of repeated dipping, pouring and drying.

While salt-making occurred on both the Atlantic and Gulf coasts, most of the salt works were on the Gulf from Tampa Bay north through the Florida Panhandle, with the biggest concentration along St. Andrews Bay in Washington County and St. Joseph's Bay in Gulf County (Calhoun County before 1925).

These bays were ideal for salt-making, containing all the resources needed for production: salt marshes, pine forests for firewood, and relative seclusion, which made it difficult for Union raiding parties to approach undetected. Salt works ranged from a few kettles to makeshift factories fired by steamboat boilers.

Along with the many Floridians engaged in the work, Alabamians and Georgians poured in to make salt. Their states also established government-owned works to supply their citizens with salt at reduced prices—the price in Atlanta, for example, was sometimes as high as $140 a sack—to compensate for rampant speculation in the trade. Florida Governor John Milton denounced the "vile spirit of speculation and extortion." He removed from sale public lands in the most lucrative salt-making areas, where speculators were buying up land to sell at exorbitant prices, and proposed a tax in-kind on in-state manufactured salt to provide for poor families. The Confederate government tried to limit speculation by establishing its own works at St. Andrews Bay, where large state-run factories produced salt for the Confederate Army.

Many of the Confederate deserters who sought refuge in Florida were joined by shirkers who claimed to be salt makers but were actually using the trade as an excuse to avoid military service. Confederate conscription laws exempted salt makers from the draft. Public outcry against phony salt makers resulted in legislative approval of Governor Milton's call to form salt workers into a militia to defend the works against Union raids. Those salt makers who refused to join the militia faced exclusion from future salt production.

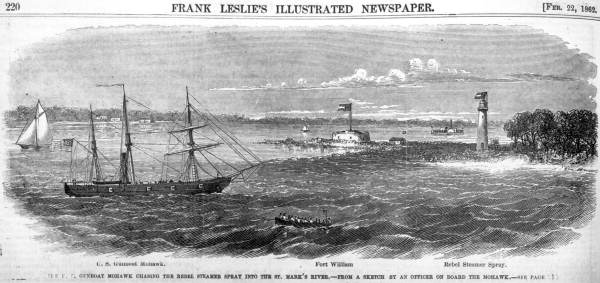

Union raiding parties did not discriminate between fake and real salt makers: The United States considered anyone engaged in the trade in the South to be an active Rebel. In 1862, the U.S. Navy began operations against salt works in Florida. The Union created two operational commands for the blockade of Florida's coast: the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, which also covered the coasts of Georgia and South Carolina, and the East Gulf Blockading Squadron, which covered the Gulf from Key West to a line just east of Pensacola. Union gunboats shelled salt-making plants and landed raiding parties to destroy the works and supplies of salt.

Hundreds of slaves worked in the salt business. Many of them built the works, supplied them with wood, stoked the fires and produced salt. While initially leery of the Union raiders, slaves eventually provided important intelligence information regarding the location of salt works. Slaves also fled to Union ships, making their way individually to gunboats or escaping the coast with Union raiding parties. Many of these "contrabands," the Union's legal term for escaped slaves, joined the U.S. Navy or enlisted in the U.S. Army. As soldiers and sailors, they joined the ranks of the salt raiders.

In November 1861, James Boyd, an engineer aboard the Union gunboat U.S.S. Albatross, wrote to his wife about some of the St. Andrews Bay raids in which he participated. A portion of Boyd's letter, which can be found in the Louis James Boyd Papers at the State Archives of Florida, is quoted (except for paragraphs and periods, without editing) below:

"…Well we left Pensacola on the 14th of this month, for [St. Andrews Bay], we arrived here on the 16th. The object of this Expedition was to destroy Salt-Pans, which the Rebels have to make Salt in. Since we have been laying here we have fit out some four or five Small Boat Expeditions, which has proven very successful. We have destroyed more Salt-Pans than all the other Expeditions put together. The Salt-Pans that I speak of are generally Situated in Small Creeks and Swamps. We cannot get to them in the Steamer [the Albatross], therefore we have to go in small Boats.

The manner in which those Expeditions are arranged are that we would leave the ships about four o'clock in the morning, and proceed up the Bay until we would discover Smoke, for that is the only way that those pans can be found by a stranger. As soon as we would get near enough we would then fire at them with a Small Cannon we have and such Skidaddeling you never seen in your life. They would leave everything behind them. We went in Several of there camps and found there Breakfast cooked and on the Table ready for eating, which our boys would soon demolish, after rowing So early in the Morning. We would then set about breaking up their pans and works …"

Boyd's account is typical of the irregular war waged on Florida's coast. Despite their frequency, the salt raids were never enough to stop Confederate salt production in Florida, which historian Robert Taylor has called "Florida's most important contribution to the Confederate economy"

See Taylor's Rebel Storehouse (University of Alabama Press, 1995), the definitive account of Florida's economic role in the war.

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "Needs More Salt." Floridiana, 2012. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/254520.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "Needs More Salt." Floridiana, 2012, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/254520. Accessed December 29, 2024.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2012, July 7). Needs More Salt. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/254520

Listen: The Gospel Program

Listen: The Gospel Program