Description of previous item

Description of next item

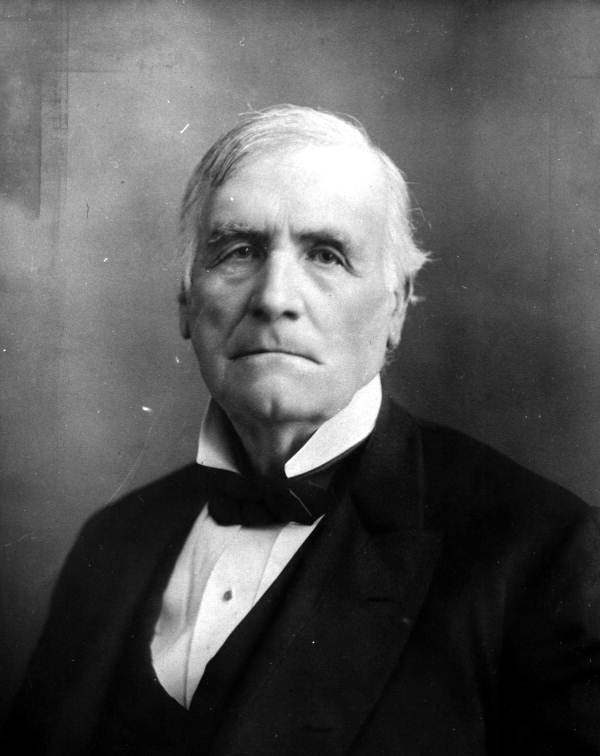

Judge William Marvin in Key West

Published April 4, 2013 by Florida Memory

On April 18, 1863, Judge William Marvin wrote President Abraham Lincoln of his wish to resign his position as "District Judge of the United States for the Southern District of Florida." Marvin had held his office since 1847, but he now wished to resign to recover his health "in a more northern climate." Judge Marvin's resignation may have only received brief notices in the Northern and Southern press, but his official career in Florida had been anything but brief or inconsequential.

From 1835, when President Andrew Jackson appointed him United States District Attorney for the Southern District of Florida, which had responsibility for federal law enforcement in all of Florida south of Port Charlotte, to his resignation of his federal judgeship in 1863, Marvin was the most important federal official in South Florida and was the only federal judge to remain in office in the South after the secession of the last states to join the Confederacy in the summer of 1861. He was the nation's top legal mind in the maritime law of wreck and salvage, represented Monroe County in the Territorial Legislative Council, served as a delegate to Florida's original constitutional convention, and was the most visible Unionist in Key West in the aftermath of Florida's secession. After the Civil War, he returned to Florida to serve as provisional governor from July-December 1865, during the initial months of the return of federal rule to the state.

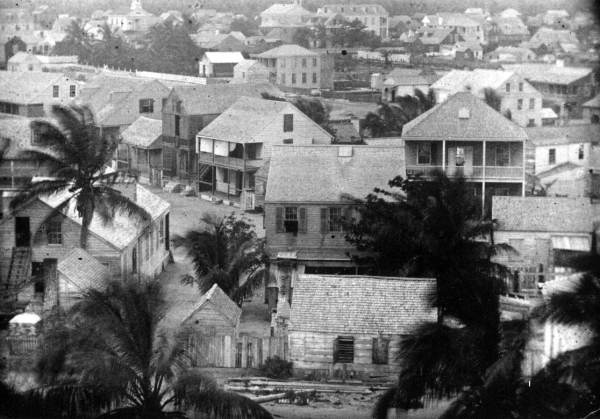

William Marvin was born in Fairfield, New York, on April 14, 1808. While still a teenager, he became a teacher and moved to Maryland, where he taught school, read law and, in 1830, became an attorney. Marvin returned to New York to practice law. In December 1834, while on legal business, he made his first trip to Florida. His voyage should have lasted five days, but bad weather turned it into an ordeal of twenty-five days, during twenty of which Marvin was seasick: "When I landed in St. Augustine I was so weak that I could scarcely walk." He remained in St. Augustine for five months, during which time he visited Jacksonville "then consisting of not more than twenty or thirty small, wooden houses and a population of, I should think, less than three hundred souls." While in St. Augustine, he met Florida's territorial delegate to Congress, Joseph White, who recommended Marvin to President Jackson for appointment as the U.S. District Attorney for the Southern District of Florida. Jackson appointed Marvin, who after a brief return to New York, sailed back to Florida in October 1835 to begin his new position in Key West.

Marvin had little work to do in his official capacity as U.S. Attorney. He soon found plenty of legal work, however, in private cases involving wreck and salvage, which was the driver of Key West's economy. Whenever a ship wrecked on the reefs off the island, "Salvors" would rush to the scene to salvage as much of the cargo as possible. The Salvors then demanded a percentage of the cargo's value as their fee for recovering items. Marvin made a lot of money representing the ship owners, who usually tried to decrease or avoid the Salvors' claims in court. When he became a federal judge, much of his time involved adjudicating these wreck and salvage cases. He became so adept at his trial work and so knowledgeable about maritime law that in 1858 he published A Treatise on the Law of Wreck and Salvage, which became the standard work on the subject.

The judge's prominence in national legal circles and in Key West society placed him in a delicate position when it came to the question of Florida's secession in December of 1860. If he chose secession, he would have to forfeit his federal judgeship and break his personal and business ties to the North; however, if he chose for the Union, he would be shunned by Key West's elite, most of whom, like fellow lawyer Stephen R. Mallory (who became Confederate Secretary of the Navy), supported the South. Even though he owned slaves as domestic servants, was a lifelong Democrat, and loved his adopted island, Marvin never believed that secession was legal and was steadfastly loyal to the idea of a perpetual Union of the states. Therefore, he "opposed the Secession Movement with all my might." He ran as a Unionist candidate in the December election of delegates for the Florida secession convention, which was to meet in Tallahassee in January 1861. Marvin lost the election and witnessed Florida's secession, and its declaration that it was henceforth "an Independent Nation."

For Marvin and countless other Americans, the time between the initial secession of Southern states to the outbreak of war was a period of "great mental anxiety and suffering." Many of his closest friends and colleagues were secessionists, and he recounted those months as the "saddest period of my life." The advent of war in April 1861 was a surprisingly fortuitous event for Marvin, who was convinced the North would win. After local Union military officials declared martial law in Key West, many of the leaders of the island's secessionist movement fled to the mainland.

Marvin reorganized the court with loyal officials. Most of his wartime work involved settling prize cases. Union warships on blockade duty off the coasts of South Carolina, Georgia, and both the Atlantic and Gulf coasts of Florida brought captured vessels suspected of blockade running to Key West. There Marvin adjudicated claims on the ship and cargo to determine if neutral nations held an interest in the vessel, its cargo, or both. If he found the ship to be owned by loyal Americans or foreigners he would release the captured vessel or "prize." However, if he found that the ship was engaged in work for the Confederates, he condemned the vessel, confiscated its cargo, and imprisoned its crew.

As Marvin mentioned in his letter to President Lincoln, by April 1863 his health required him to resign his judgeship. He finally left his office in July 1863, after a successor was found to take his place. Marvin returned to New York with his family. His wife, Harriette N. Foote, died in 1848, leaving one child, Hattie, who grew up in Key West and accompanied her father back to New York. In July, 1865, President Andrew Johnson appointed Marvin provisional governor of Florida.

Marvin worked to bring Florida back into the Union and guided the work of the first postwar constitutional convention. He supported the state's adoption of the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery, but did not support giving the vote to African-Americans. He was also willing to recommend pardons for a number of Florida's top Confederate officials. Although he was elected one of Florida's first U.S. Senators under Reconstruction, he never took office. The Senate, in the control of the Radical Republican majority, refused to admit Marvin and other Southern senators whose states had not enfranchised African-Americans. In 1867, Marvin returned to New York to live in the phonetically challenged town of Skaneateles, where he died at age 94 in 1902.

Marvin's resignation letter to Lincoln is available in The Papers of Abraham Lincoln and located in Box 3, Entry 9A, Records of the Attorney General's Office: Letters Received, 1809-1870. Presidents Letters 1814-1870. National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C. Marvin quotes come from his 1892 memoir, "Autobiography of William Marvin," edited by Kevin E. Kearney in the Florida Historical Quarterly 36 (January 1958): 179-222.

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "Judge William Marvin in Key West." Floridiana, 2013. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/258778.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "Judge William Marvin in Key West." Floridiana, 2013, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/258778. Accessed December 28, 2024.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2013, April 4). Judge William Marvin in Key West. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/258778

Listen: The World Program

Listen: The World Program