Florida Memory is administered by the Florida Department of State, Division of Library and Information Services, Bureau of Archives and Records Management. The digitized records on Florida Memory come from the collections of the State Archives of Florida and the special collections of the State Library of Florida.

State Archives of Florida

- ArchivesFlorida.com

- State Archives Online Catalog

- ArchivesFlorida.com

- ArchivesFlorida.com

State Library of Florida

Related Sites

Description of previous item

Description of next item

Lower Court

Date

Box

Folder

Transcript

State of Florida

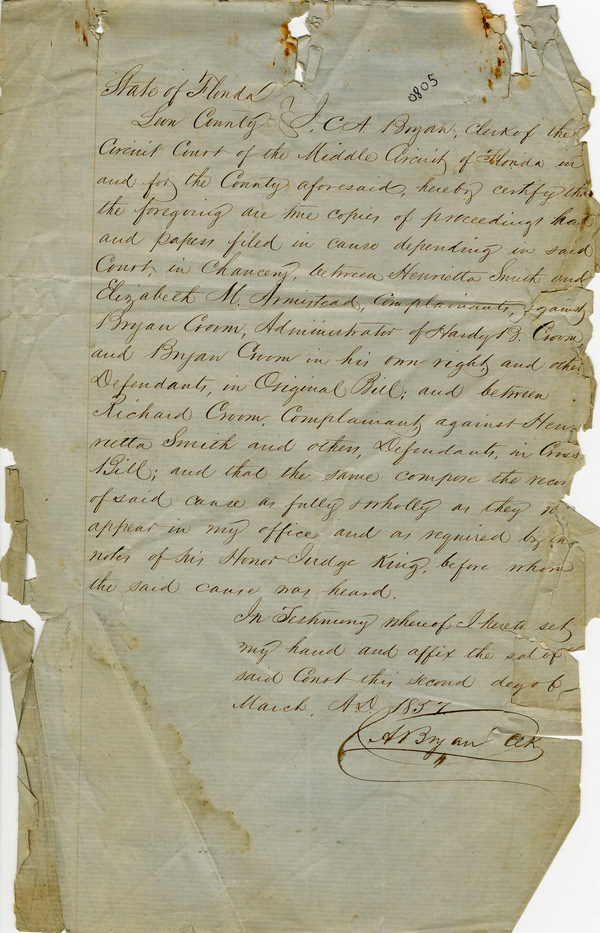

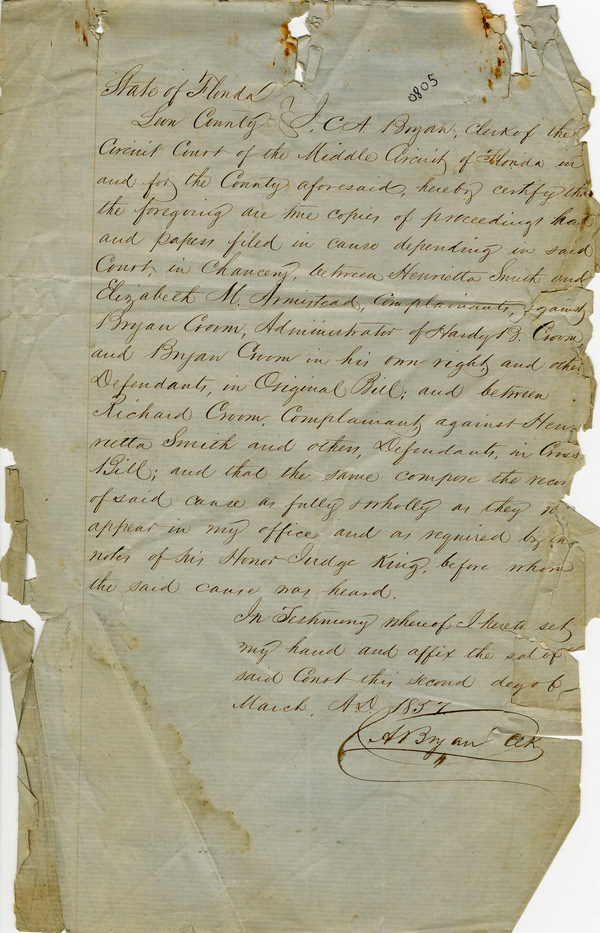

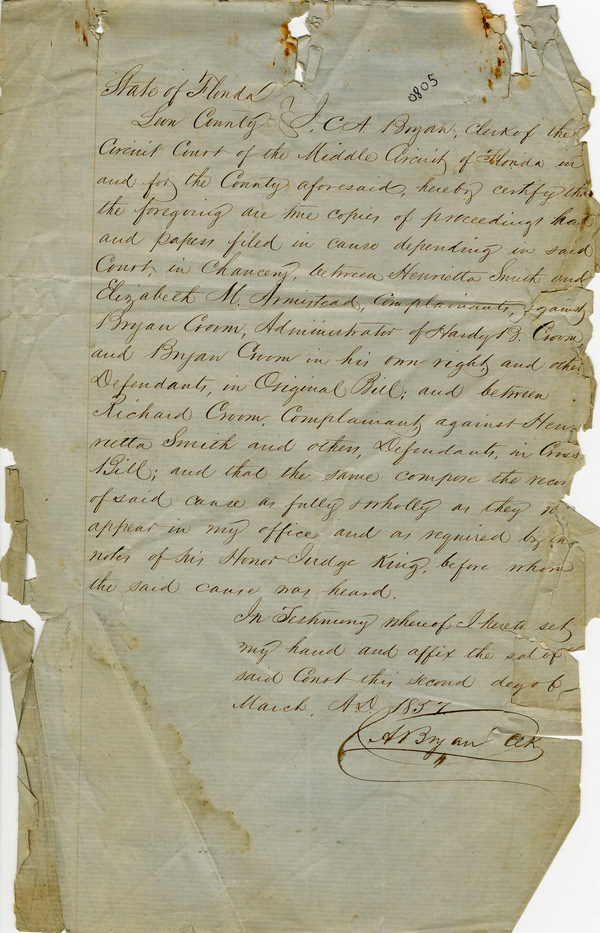

Leon County ??? Bryan clerk of the Circuit Court of the Middle Circuit of Florida in and for the County aforesaid, hereby certify that the foregoing are true copies of proceedings had and paper filed in cause depending in said Court in Chancery, between Henrietta Smith and Elizabeth M. Armistead, Complainants, against Bryan Croom, Administrator of Hardy B. Croom and Bryan Croom in his right and other Defendants, in Original Bill; and between Richard Croom, Complainant, against Henrietta Smith and others, Defendants in Cross Bill; and that the same compose the record of said cause as fully & wholly as they ??? appear in my office and as required by ??? notes of his Honor Judge King, before whom the said cause was heard. In testimony whereof I hereto set my hand and affix the sale of said Court this second day of March A.D. 1857

A.Bryan Clerk

Title

Subject

Description

Among those lost were Hardy Bryan Croom, his wife Frances, and their three children. All of them were swept into the sea and drowned. Their deaths were the catalyst of a legal dispute that lasted nearly a quarter century and set lasting precedent in probate law.

Hardy B. Croom was a wealthy planter born in Lenoir County, North Carolina, the son of General William Croom. He was a graduate of the University of North Carolina and studied law, but was also interested in the sciences, especially botany. After the death of his father in 1829, he sold his Lenoir County plantation and moved most of his slaves to the North Florida land holdings inherited from his father. Between 1830 and 1837 he frequently traveled between New Bern, New York, Charleston, and Florida to manage his business interests.

Croom was very interested in Florida flora and is credited with the discovery of the Torreya tree, which he named after his friend Dr. John Torrey of New York. He made the discovery while traveling between his land holdings in the Tallahassee area and his plantation at the Apalachicola River.

In 1837, he made the decision to bring his family to Florida for the winter months. He and his family secured passage on the steamship Home to travel from New York to Charleston, South Carolina, and intended to travel overland from there to Tallahassee.

If Hardy B. Croom wrote a will, it was never found. His brother Bryan Croom was appointed administrator of his Florida estate, but the deceased children's maternal grandmother and executor of their estate in North Carolina, Henrietta Smith, and their mother's sister, Mrs. Elizabeth Armistead, filed a bill in Leon Circuit Court against the siblings of Hardy Croom that disputed their claim on the basis of legal residence.

Florida territorial law awarded property in probate cases along the paternal line. If Croom's legal residence was in Florida, he survived his wife and children in the disaster and then died without a will, his relatives, in this case brothers and a sister, would inherit all of his real property.

However, under North Carolina law, if his legal residence was in North Carolina and any of his children survived him, his estate would pass to them. Upon the children's deaths, their grandmother would inherit the estate as the next of kin. And under Florida law, the petitioners as next of kin would also be entitled to real estate in Florida.

The key questions in this case were first: was legal residence of Hardy Croom, and by extension his family, in North Carolina or Florida? Second, who survived the shipwreck the longest?

The court determined, after reviewing correspondence going back years between members of the Croom family, that he had not abandoned his domicile in New Bern. As stated in the case,

"When the domicil of origin is ascertained, it attaches to the person until the new domicil is acquired facto et animo. The mere intention to acquire a new domicil, unaccompanied by an actual removal, avails nothing, neither does the fact of removal without the intention avail.

"The place where a married man" family resides is generally to be deemed his domicil, but the presumption from this circumstance may be controlled by other circumstances.

Where a party abandons the domicil of origin in fact and with a present intention to acquire a new one, if he dies in itinerae, and before he has consummated that intention by an actual residence, the domicil of origin immediately reverts and re-attaches."

The family had not completed their move to either Charleston, as the Crooms had contemplated, nor Florida, thus their home remained in New Bern.

To explore the second question, the lawyers in the case were able to assemble eleven survivors of the wreck as witnesses to determine the order in which members of the Croom family died. The court heard testimony about the shipwreck and when members of the Croom family were last seen. The witnesses indicated that Mrs. Croom, her aunt Mrs. Carmack who had been traveling with them, and the youngest daughter, Justina, were washed into the sea first and not seen again. Mr. Croom was washed overboard next. The oldest daughter, Henrietta, had managed to get to the wheelhouse and clung there until it collapsed. The son, William Henry, was on the promenade deck when it separated from the rest of the ship and was sighted clinging to wreckage before it grounded and he drowned trying to reach the shore.

The lower court had been presented testimony that Hardy Croom was a strong swimmer, and also conflicting testimony that he was a feeble man of ill health that would have been exhausted easily. It decided that he had survived the rest of his family before drowning, and awarded the estate to Croom's brother Bryan and his siblings.

In 1857, 20 years after the disaster, the Supreme Court reversed the decision of the lower court and held that Hardy Croom survived his wife and younger daughter, that Henrietta and William survived their father, and that William was the last survivor of his family. The court also held that the legal domicile of Hardy Croom and his children on the date of his death was in the state of North Carolina.

Under this decision, Henrietta Smith, the mother of Mrs. Croom, inherited all the personal property and one-eighth of the real estate. Mrs. Armistead, aunt of the children, was also awarded one-eighth of the real estate. The heirs of Hardy Croom received the remaining three-fourths of the real estate under the laws of North Carolina.

In the Croom case the Supreme Court of Florida recognized the common law of England, adopted by the Legislative Council of Florida in 1829, in the following language:

"In a question of survivorship arising out of a common calamity the legal presumption founded upon the circumstances of age, size or physical strength does not stand in our jurisprudence, either as a doctrine of the common law or as an enactment of the legislative authority. It is a doctrine of the civil law."

"But when the calamity, though common to all, consists of a series of successive events, separated from each other in point of time and character and each likely to produce death upon the several victims according to the degree of exposure to it, in each case the difference of age, sex and physical strength becomes a matter of evidence and may be considered."

The wreck of the SS Home was one of the causes that induced Congress to pass the Steamboat Act, effective October 1, 1838. The Act provided for steamship inspections to improve the security of the lives of passengers on board vessels propelled in whole or in part by steam.

Creator

Source

Date

Format

Language

Type

Identifier

Folder

Box

Lower Court

Total Images

Image Path

Image Path - Large

Transcript Path

Thumbnail

Chicago Manual of Style

Florida Supreme Court. Smith v. Croom. 1839. State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory. <https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/260675>, accessed 28 December 2024.

MLA

Florida Supreme Court. Smith v. Croom. 1839. State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory. Accessed 28 Dec. 2024.<https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/260675>

AP Style Photo Citation

(State Archives of Florida/Florida Supreme Court)

Listen: The Latin Program

Listen: The Latin Program