Description of previous item

Description of next item

Camp Roosevelt

Published July 7, 2014 by Florida Memory

Every old house, every river, and every bend in the road in Florida has a story. Some are easy to learn about, others not so much. Understanding the history of a place becomes even more complicated when the place itself changes rapidly over a short period of time. The history of Camp Roosevelt south of Ocala is a case in point. In the space of a single decade, it served as an educational center for at least three separate federal programs, headquarters for workers building the Cross-Florida Barge Canal, and emergency housing for returning World War II veterans and their families.

Map showing the location of Camp Roosevelt just south of Ocala near the convergence of Lake Weir Rd. with U.S. 27/301/441. The map dates to the 1990s, but the Roosevelt name remains.

The camp originated as a temporary home for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the large labor force it needed to build the Cross-Florida Barge Canal. This project had been a long time in the making. Even as far back as the 16th century when the Spanish had control of Florida, shippers and government officials had wished there was some way to shorten the lengthy and dangerous voyage necessary to sail around the Florida Straits. A number of ideas emerged for digging the canal, but the enormous expense of the project led private and public authorities to shy away from it.

Ironically, the arrival of the Great Depression gave the plan a boost off the drawing board and into action. Local politicians urged the federal government to take on the canal project as a federal relief program through the New Deal. The Franklin Roosevelt administration allocated funding for the project in September 1935 on this basis, and by the end of the month construction was underway to prepare for workers to arrive. The plans called for what amounted to a small city, complete with medical and recreational facilities, a dining hall, a post office, and headquarters buildings. The Army Corps of Engineers designated the site as “Camp Roosevelt” in honor of the President.

Men’s dormitory at Camp Roosevelt, built in 1935 to accommodate workers for the Cross-Florida Barge Canal (photo circa 1936).

The camp’s population quickly swelled with workers, but their stay was to be much shorter than planners had expected. Vocal opponents of the project in Central and South Florida argued that digging the deep canal would expose and contaminate the underground aquifer that contained their water supply. Sensing trouble, the Roosevelt administration quietly backed off of the project. Works Progress Administrator Harold Ickes dropped his support, and Congress failed to extend the original 1935 appropriation. In the summer of 1936, with only preliminary work complete in several locations along the proposed route, work came to a halt.

With no money to continue, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers prepared to close its operations at Camp Roosevelt. With these extensive facilities vacant, the Works Progress Administration sensed an opportunity to take over the site and use it for a good cause. The W.P.A., the University of Florida in Gainesville, and the Army Corps of Engineers reached an agreement whereby the University would operate Camp Roosevelt as a center for adult education. The University would be in charge of the program itself, whereas the W.P.A. would handle the business end of the camp. The Army Corps of Engineers would pay most of the utility bills. Less than three months from the end of the work on the barge canal, the University of Florida’s adult education extension program was up and running at the camp. Major Bert Clair Riley, the university’s dean of extension services, administered the program from Gainesville, while a series of local directors handled the day-to-day business on the ground.

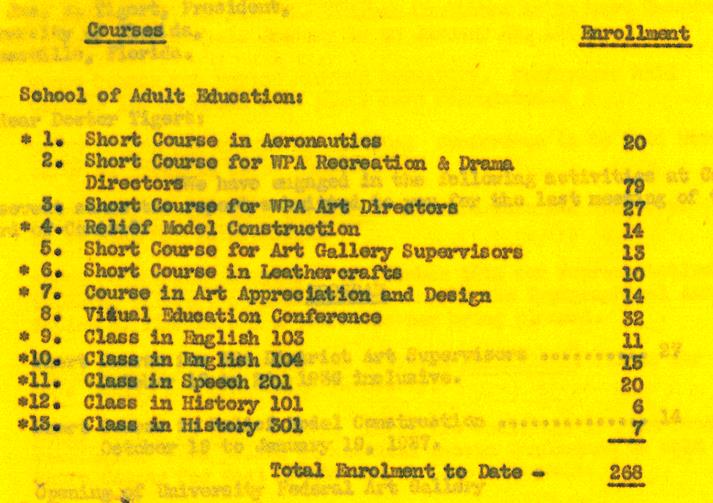

At first, the extension program mainly offered short courses in subjects like model design, leathercraft, art appreciation and design, and training for W.P.A. administrators. Program leaders made bold plans to expand their reach to include short courses for civic officials, printers, real estate brokers, toymakers, and aviators. The University also offered more formal courses in subjects like English and History to aid those students who wished to continue their education at the university level.

A list of classes held during one of the first terms conducted by the University of Florida extension program at Camp Roosevelt, fall 1936. This document is part of the records of Camp Roosevelt held by the State Archives of Florida (Series M87-9).

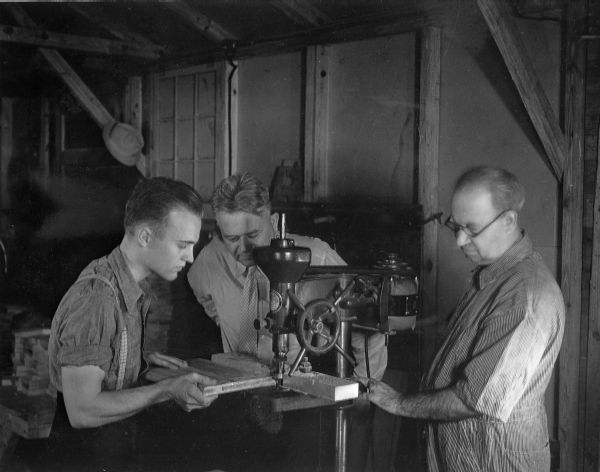

Funding for the extension program, as with the canal and so many federal projects at this time, was temporary, and within a year the University of Florida had to decide whether it would continue the work. It did, in a way, but through a new partnership that changed the focus of the camp to more of a relief operation. The National Youth Administration, dreamed up by Eleanor Roosevelt as a way to offer federal relief to young women who could not join the Civilian Conservation Corps, teamed up with the vocational division of the Marion County school system and began running the camp. The camp’s population consisted mainly of women, although men would later be admitted to the camp as well. Participants took classes for half the day, and worked on projects such as sewing, metalwork, or cosmetology for the remainder of the day. Typically, the students had had no more than a year or two of high school before entering Camp Roosevelt. By the time they completed the term, program administrators hoped to place them in their communities as secretaries, stenographers, library assistants, or other skilled workers.

As World War II approached, the camp’s classes and activities became geared more toward defense work. Teenage boys too young to enter the military were admitted to the camp, and nursing, welding, woodwork, and signmaking replaced the more domestic skills that had been prevalent in earlier years.

Whether they came for the federal relief wages or to do defense work, Camp Roosevelt’s residents were living in a difficult time. This did not, however, stop them from making the best of their situation and maintaining a healthy social atmosphere. The camp had a newsletter, the “Roosevelt Roundup,” edited by the faculty and students. It had dances and athletic activities, and recreation leadership training was even offered as a course.

As the war continued, more and more of Camp Roosevelt’s usual pool of residents became involved in formal defense work, and administrators decided to shut the camp down. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers retained the site and planned to keep it up, as plenty of enthusiasm still remained for resuming the Cross-Florida Barge Canal project. Before that could happen, however, a more pressing problem emerged for the camp to tackle.

As World War II came to a close, the young men and women who had left to join the military or serve in other defense capacities came home, looking to start new lives as adult civilians. This sudden surge triggered a dire shortage of adequate housing. Husbands and wives and sometimes children frequently found themselves living with other family members, not so much for lack of funds but simply for lack of available homes to buy or rent. Civic leaders scrambled for solutions, and in Marion County facilities like the small houses at Camp Roosevelt became an attractive option. The Ocala/Marion County Chamber of Commerce appealed to federal leaders, asking that the buildings at Camp Roosevelt be made available to provide housing for returning veterans. Washington complied, and soon former soldiers and their young families were moving into the buildings once occupied by canal workers and then residents of the W.P.A. and N.Y.A. relief programs. The federal government retained the right to move the new residents should the barge canal project regenerate, but by the time this happened some years later, the Army Corps of Engineers had determined it would not need the complex. It was declared surplus property, and eventually was sold piecemeal to private citizens.

One of over seventy residences at Camp Roosevelt built originally to house workers for the Cross-Florida Barge Canal project. Many of these homes were later sold to private citizens and became part of the Roosevelt Village neighborhood (photo circa 1936).

Looking at this neighborhood, now called Roosevelt Village, its former roles during the Great Depression and World War II are not readily apparent. It just goes to show that no matter which direction you look in Florida, there’s a story to be told.

What buildings or other spaces in your Florida town played a role in the Great Depression or World War II? Search the Florida Photographic Collection to see what photos the State Archives may have of those places.

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "Camp Roosevelt." Floridiana, 2014. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/295197.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "Camp Roosevelt." Floridiana, 2014, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/295197. Accessed December 28, 2024.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2014, July 7). Camp Roosevelt. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/295197

Listen: The Latin Program

Listen: The Latin Program