Description of previous item

Description of next item

Old Sparky's Rough Start: The Story of Jim Williams

Published September 9, 2014 by Florida Memory

The curious story of Jim Williams begins with an early, botched operation of “Old Sparky,” Florida’s electric chair, and ends on the lips of a folk singer, with plenty of misinterpretation, heroics, and history in between.

On April 10, 1926, Jim Williams, a 25 year-old African-American man living in Palatka in Putnam County, Florida, was convicted of murdering his wife and sentenced to death by electrocution. His execution was scheduled for June 1, 1926 the Florida State Prison at Raiford.

On the day of the execution, Williams was strapped into what would become known as Old Sparky. As Williams awaited his fate, an argument erupted over who should throw the switch that would end his life. After many minutes and no resolution, prison superintendent James Simeon Blitch contacted Governor John Martin for an answer.

James Simeon Blitch, superintendent of Florida State Prison at Raiford, FL in 1926. Photograph by Jack Spottswood.

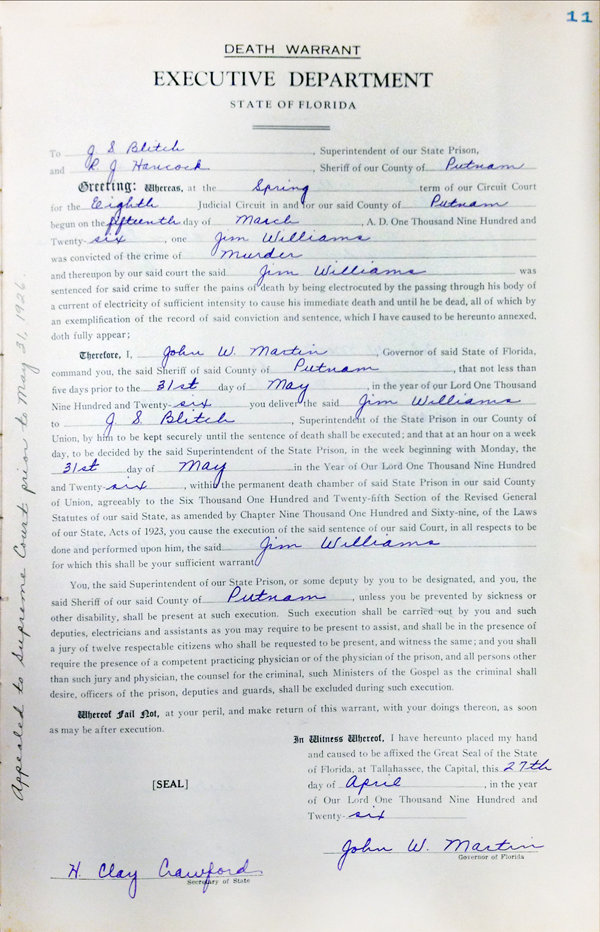

The problem derived from unclear language in the death warrant regarding who was to carry out the execution. The official document, signed by Governor Martin and addressed to both Superintendent Blitch and Putnam County Sheriff R.J. Hancock, gave these instructions:

“You, the said Superintendent of our State Prison, or some deputy by you to be designated, and you, the said sheriff of our said County of Putnam, unless you be prevented by sickness or other disability, shall be present at such execution. Such execution shall be carried out by you and such deputies, electricians and assistants as you may require to be present to assist…”

The warrant clearly required the presence of both men, but it did not specify which would serve as the executioner. Newspapers reported that the sheriff of the county in which the crime was committed was the official obliged to end the life of the condemned. In Williams’ case it would be Putnam County Sheriff R.J. Hancock. However, Hancock added to the confusion by sending two deputies, Walter Minton and L. Shannon in his place, and both men refused to carry out the execution. Superintendent Blitch was also unwilling to throw the switch. Given the uncertainty and confusion, Governor Martin instructed Blitch to return Jim Williams to his cell. Ultimately, despite two additional death warrants, Williams’ sentence was commuted to life imprisonment, but his story does not stop there.

As officials deliberated over who would serve as executioner, Williams’ sat in the chair terrified. His brush with death had a profound effect, as one would imagine. Attorney General (and later Florida Supreme Court Justice) Fred. H. Davis, said after visiting Raiford in 1927, “They can’t get him to sit in a barber’s chair because it looks a bit like the electric chair. He steadfastly refuses to undergo any tonsorial operations and I shouldn’t be surprised if it would not take the whole prison population to make him do it.”.

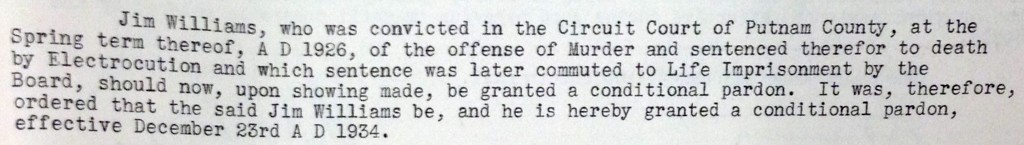

According to newspapers, in 1934, Williams jumped from a moving convict truck to save a woman and her child from a mad bull. He was granted a conditional pardon for his heroism and was released December 23, 1934. Although the details of his heroism are uncertain, the pardon issued by Governor Fred Cone is well-documented.

Text of the conditional pardon issued by Governor Cone from the minutes of the the Florida Board of Pardons.

After his release, he was never heard from again. Oddities promoter Robert Ripley, creator of Ripley’s Believe It or Not, offered a $500 reward for information about the whereabouts of Jim Williams calling him “the only person ever known to have been strapped in the electric chair and escape execution.”

Florida’s “Black Hat Troubadour”, Will McLean wrote a ballad telling the story of Jim Williams. While the story is that of Williams, McLean names him incorrectly as Abraham Washington, another death row escapee. The first verse refers to Washington’s story, while the rest is that of Williams. Abraham Washington was, as McLean sings, sentenced to death by hanging shortly before a new law requiring the use of the electric chair. The death warrant was declared void by the Duval County court because it specified that Washington was to hang, not be electrocuted, and hanging had been outlawed. The case went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. By that time, Washington’s sentence had been commuted to life imprisonment.

Abraham Washington

Well there was a man named Washington, his first name Abraham

The judge said he would ride the rope into the Promised Land

Before he met his fateful doom, the hanging law was dead

They took him down to Raiford-town to the electric chair insteadThey strapped him in the electric chair and so while he was waitin’

The warden and the county sheriff were talkin’ and debatin’

Which one of us must throw the switch and send this man to Hell?

But no decision could be reached; in prison he would dwell

They took him from the electric chair, his sweat had turned to blood

They told him that his life was spared and from his eyes did flood

the salty tears of gratefulness; it happens to all men

Down on his knees he made this vow to never sit againOne day a prison gang did ride by pastures that were green

A mother with her baby strolled so happy and serene

Suddenly a vicious bull did charge this freighted wife

And Abraham, he jumped the fence and saved this woman’s lifeA pardon full to Washington, his first name Abraham

Who took a vow to never sit again while on this land

The last account of Washington, the day was cold and wet,

was Abraham, have you kept your vow? And he said “I ain’t sat yet.”

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "Old Sparky's Rough Start: The Story of Jim Williams." Floridiana, 2014. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/295212.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "Old Sparky's Rough Start: The Story of Jim Williams." Floridiana, 2014, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/295212. Accessed December 29, 2024.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2014, September 9). Old Sparky's Rough Start: The Story of Jim Williams. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/295212

Listen: The Gospel Program

Listen: The Gospel Program