Description of previous item

Description of next item

Not on MY Biscuit!

Published January 1, 2016 by Florida Memory

Do you use butter in your home, or do you prefer margarine? The stakes involved in this question may seem rather low, but that’s not how dairy farmers saw things when margarine came on the scene in the 1870s. They were accustomed, after all, to selling most of the nation’s butter that wasn’t being produced at home. In Florida and elsewhere, the question of whether and how to regulate margarine ultimately fell to lawmakers to decide, resulting in a real 19th century “bitter butter battle.”

Edvis Newton stands with a Parkay margarine display at a Jitney Jungle store in Tallahassee (1947). Who knew such a popular product had such a contentious history?

A French chemist named Hippolyte Mège-Mouriès invented margarine in the 1860s in response to a contest sponsored by Emperor Napoleon III to develop a suitable substitute for butter. The emperor hoped the winning substance could be used by the lower classes and the French military. Mège-Mouriès called his solution “oleomargarine.” The “oleo” part came from the Latin oleum (oil), since one of the major components of the product was beef tallow. The “margarine” part of the name came from the margaric acid used in creating the compound. The term “margaric” is adapted from the Greek word márgaron, meaning “pearl” or “pearl-oyster,” since the fatty acid naturally forms small white pearl-shaped droplets.

Mège-Mouriès patented his new product and marketed it under the trade name “margarine.” The idea caught on well enough to cross the Atlantic Ocean, and by 1871 inventors were already seeking patents for margarine production processes in the United States. Meatpackers were some of margarine’s most enthusiastic proponents, since the new product gave them something profitable to do with the animal fats leftover from processing meat. Dairy farmers, on the other hand, saw margarine as a threat to their hold on the butter market. They were joined in their opposition by others who were concerned that improperly concocted margarine could be dangerous to human health.

The question of what to do about butter and its imitators began landing in state legislatures across the nation, and in 1881 it was Florida’s turn to debate the matter. The following law passed the Senate and Assembly and was approved by signature of Governor William D. Bloxham on February 17, 1881:

AN ACT to prevent the selling as Butter of Oleomargarine or any Spurious Preparations purporting to be Butter.

The People of the State of Florida, represented in Senate and Assembly, do enact as follows: SECTION 1. That any person or persons who shall knowingly and willingly sell or cause to be sold as butter any spurious preparation purporting to be butter, whether known as oleomargarine or by any other name, shall be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor, and upon conviction shall be fined in a sum not to exceed one hundred dollars, or be imprisoned in the county jail for a period of time not to exceed thirty days, or by both fine and imprisonment, at the discretion of the Court.

SEC 2. Any keeper of any hotel or boarding house who shall knowingly and wilfully, without giving notice to guests at the table, supply oleomargarine or other spurious preparation purporting to be butter, for the use of guests, shall be subject to the same penalty.

That’s a stiff punishment for passing fake butter!

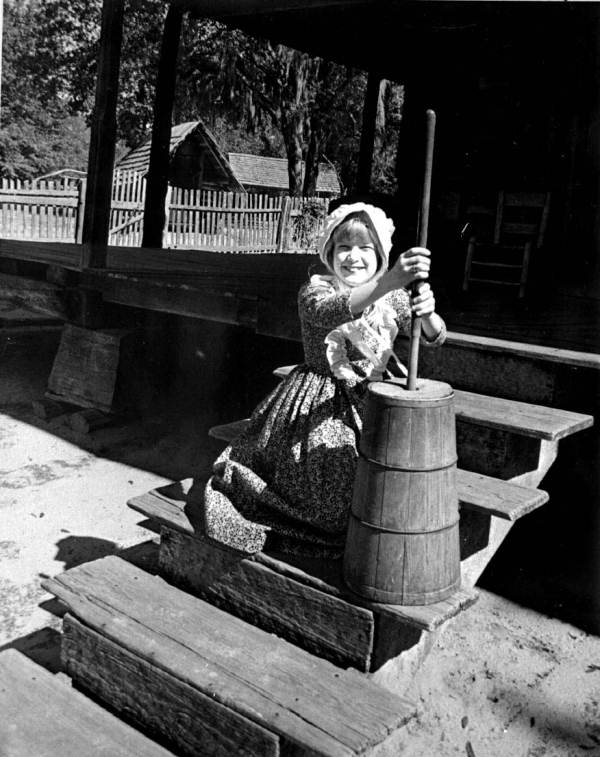

No margarine here! Young Margie Davis is seen here churning butter the old-fashioned way (date unknown).

Taken in context, Florida’s treatment of margarine was not so unusual. Congress adopted a law in 1886 regulating the definition of butter and imposing a tax on oleomargarine at two cents per pound. State governments developed a whole range of solutions to the butter battle, including restricting producers from coloring margarine to resemble butter. Without coloring, margarine typically has a whitish tint, resembling lard more than butter. Delaware, Illinois, and Michigan all passed laws establishing this sort of color restriction. New Hampshire opted for the opposite tactic. Its legislature required margarine producers to color their products pink, so consumers would realize they weren’t eating real butter.

Despite all the fuss, consumers gradually warmed up to the idea of using margarine, especially in situations when meat, milk, and butter were in short supply. City dwellers who lacked easy, inexpensive access to farm-fresh butter tended to favor the margarine substitute, and it served as a vital commodity during both world wars. By the 1950s, most of the earlier restrictions on margarine had been dropped.

Margarine has also served at times as creative inspiration. Census and Social Security Death Index records indicate that Florida has been home to many people with some variant of the term “oleomargarine” in their names over the years. The words “Oleo” and “Margarine” were quite common by themselves as names in the early decades of the 20th century, while our research has turned up one case in Duval County of someone with “Oleo Margarine” as their full given name.

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "Not on MY Biscuit!." Floridiana, 2016. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/321967.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "Not on MY Biscuit!." Floridiana, 2016, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/321967. Accessed December 29, 2024.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2016, January 1). Not on MY Biscuit!. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/321967

Listen: The Gospel Program

Listen: The Gospel Program