Description of previous item

Description of next item

Miss Nancy's Story

Published June 6, 2017 by Florida Memory

This is one of two Floridiana articles highlighting the Nancy Tribble Benda Collection (N2016-1) available at the State Archives of Florida. Benda was one of the first mermaids to perform at Weeki Wachee Springs when it opened in 1947. She later went on to star in WFSU-TV’s educational children’s television show “Miss Nancy’s Store” from 1966-1967 before working for the Florida Department of Education.

After splashing onto the scene in the 1940s as one of the first-ever Weeki Wachee mermaids, Nancy Tribble Benda briefly stepped out of the limelight to pursue a degree in elementary education at Florida State University (FSU). But by the 1960s she was making waves again. This time as the star of her own educational television show: The hit children’s series “Miss Nancy’s Store” aired on WFSU-TV from 1966-1967. During an illustrious 40-year public education career, Benda worked both on and off-screen to expand educational access in Florida.

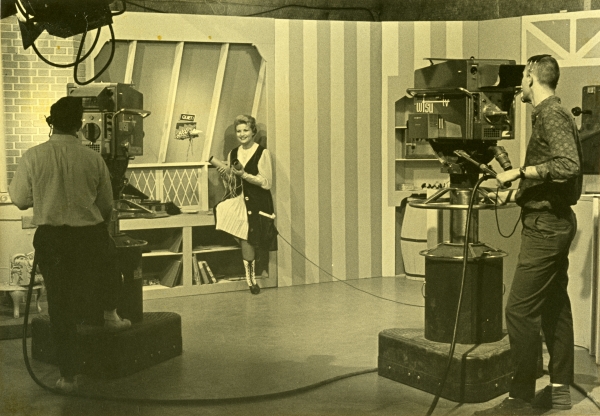

Nancy Tribble Benda on the set of WFSU-TV’s educational children’s television show, “Miss Nancy’s Store,” ca. 1966.

Nancy Tribble was born in 1930. Back then, radio was king and television was still a new-fangled experiment. But by the time a teen-aged Ms. Tribble landed her role as an underwater entertainer at the new Weeki Wachee Springs amusement park in Brooksville, Florida, in 1947, home television sets had debuted in American markets. Over the next decade, as television began to redefine national media consumption, it would also redirect Benda’s career path.

Shortly after appearing in the 1948 motion picture Mr. Peabody and the Mermaid, Benda hung up her mermaid fin and moved back to her hometown of Tallahassee, where she enrolled at Florida State University. She married architect Charles Benda in 1950. After graduation, Mrs. Nancy Tribble Benda took her first job at Havana Elementary School in Gadsden County, teaching fifth grade. A few years later, she transferred to Sealey Memorial Elementary in Leon County. But Benda wouldn’t stay in a traditional classroom for long. Her combined performance and teaching talents would soon thrust her into the emerging educational television industry.

Benda (second row, right) at the Alpha Xi Delta Sorority rush party at Florida State University, ca. 1949.

Ed. Television Comes to Florida

By 1955, half of American households owned a television. Big networks such as ABC, CBS, and NBC captivated audiences with the comedic cheese of family sit-coms like The Goldbergs, Leave it to Beaver, and I Love Lucy. However, heavy product placement, gimmicky ads and implausible story lines left some parents and professionals concerned that the first generation of American youngsters to grow up in front of the television were starved for intellectual stimulation.

The answer to the call for more educational television programming first arrived in 1952 with the creation of the Educational Television and Radio Center (later renamed National Educational Television and replaced by the Public Broadcasting Service in 1970). The network aimed to educate the nation’s growing number of television viewers with an entertaining yet enriching lineup. Proponents saw potential in the new technology’s unprecedented ability to provide underserved populations with quality educational programming.

Individual states soon caught on to the idea of “teleducation,” developing the first statewide educational television networks in the 1950s. Florida’s population increased enormously after World War II, ballooning from just under 2 million in 1940 to 3.7 million by 1955. The dramatic influx of new residents overburdened the state’s traditional public education infrastructure. Consequently, Florida Governor LeRoy Collins, who was elected in 1954 on a progressive education platform, looked to the remote access afforded by educational television programming as a possible solution.

In 1957, the Florida Legislature created the Florida Educational Television Commission (Ch. 57-312, Laws) “to provide through educational television a means of extending the powers of teaching in public education and of raising living and educational standards of the citizens and residents of the state.”

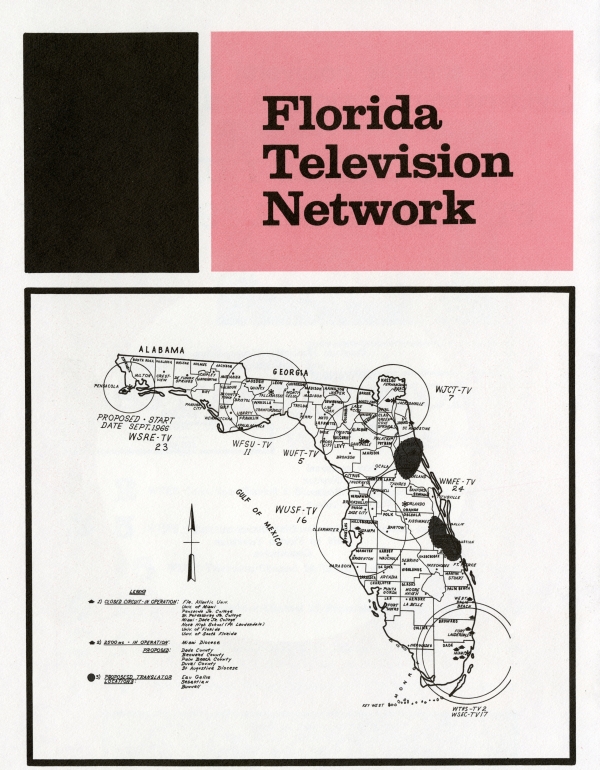

The commission joined with state universities and the independent Florida Institute for Continuing University Studies (FICUS) to create the Florida Television Network. The entity produced both closed-circuit and public access educational programming to enhance learning in all levels of public education, from kindergarten to adult learning.

Illustration showing the radial reach of the Florida Television Network’s six stations, ca. 1966. Nancy Benda Collection (N2016-1), Box 05, Folder 9, State Archives of Florida. Click to enlarge and view full record.

Some channels also collaborated with local school boards. WTHS-TV in Miami opened the first school board-run station in the country in 1957, serving students enrolled in district by day and the general public by night. In 1960 WFSU-TV, whose production studios were located on FSU’s campus, went live in Tallahassee.

By 1965, six non-commercial broadcast stations were in operation throughout Florida: Tallahassee, Gainesville, Miami, Tampa, Jacksonville and Orlando.

Tallahassee’s T.V. Teacher

Benda’s role in the rising educational television movement started in 1960, when she took a continuing education summer school class on the “techniques” of educational television. The following year, she and several other local Leon County elementary school teachers formulated a curriculum for a televised fifth grade social studies course for students in the district.

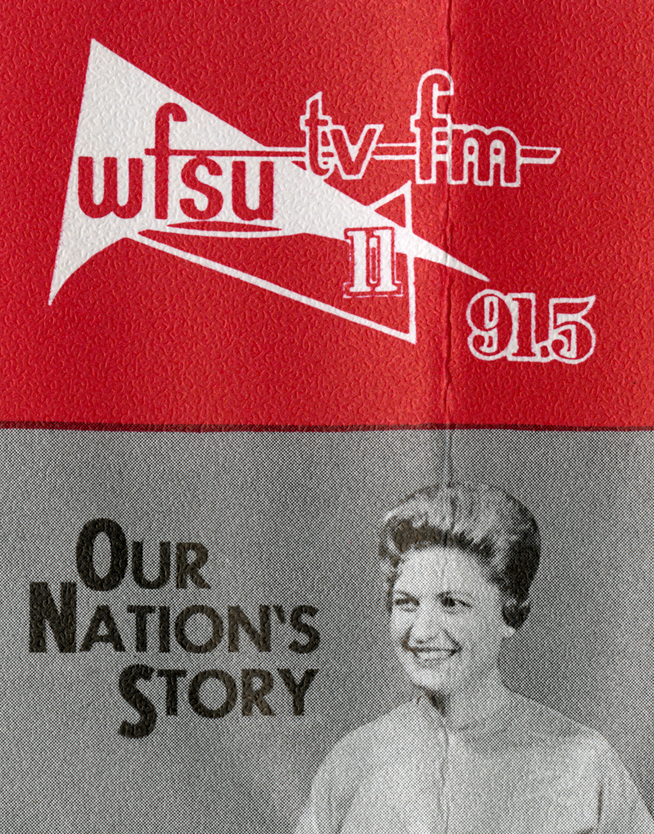

Once the Leon County School Board approved the new social studies course, the school board held auditions for an on-air teaching position and Benda won the part. On February 1, 1962, the first episode of the live history-themed puppet show, “Our Nation’s Story,” premiered on WFSU-TV’s Channel 11. During the course, which aired every Tuesday and Thursday at 2:00 p.m. in fifth grade social studies classrooms throughout Leon County, Benda taught lessons on the history of the United States from “the westward movement in the late 1840s … to [the] beginnings] [of] space travel.”

WFSU-TV program guide featuring an advertisement for “Our Nation’s Story,” 1963. Nancy Benda Collection (N2016-1), Box 05, Folder 9, State Archives of Florida. Click to enlarge and view full record.

WFSU-TV’s reach expanded quickly to the rural counties surrounding Leon County, including Calhoun, Gulf, Jackson, Liberty and Wakulla counties. The program supplemented traditional classroom material and helped break down educational access barriers, serving an estimated 6,000 viewers in the Big Bend area.

“We want to be sure we’re fulfilling a need and we want to put TV to best use,” Benda said. The school board eventually approved Benda’s transfer from Sealey Elementary to full-time status as a television teacher. Only responsible for teaching one course, the state’s handful of TV teachers were able to devote more time to enhancing their lessons and making them more engaging for students. Additionally, TV teachers could fill in if a school did not have a teacher qualified to teach a particular course.

Before long, Benda was appearing on Florida’s other five regional public television stations as part of the network’s statewide educational programming initiative, “Through the TV Tube,” which offered for-credit elementary, secondary and college telecourses. Benda taught televised elementary level American history and science classes. The network also offered Spanish, physical education,reading, literature, art, writing and speech courses. Additionally, many Florida high schoolers tuned in to watch a televised version of the legislatively mandated six-week high school course, Americanism vs. Communism. The Cold War-era content remained a public school curriculum requirement until 1983 when lawmakers replaced it with an essential economics class.

Letter from the Florida Institute for Continuing University Studies to Nancy Benda thanking the teacher for her work on “Through the TV Tube” with a “small honorarium,” August 3, 1964. Nancy Benda Collection N2016-1, Box 05, Folder 1, State Archives of Florida.

Florida’s innovative educational television programming garnered high praise from national critics. Nancy Benda won the 1965 Freedoms Foundation Award for her work on “Our Nation’s Story.”

Additionally, Television Digest touted the Florida networks’ expansive coverage, writing in 1964 that “Despite much talk by other states about elaborate, proposed ETV systems, Florida is still the only state to achieve anything like a real statewide network with programs available to significant numbers of major population areas.”

Benda’s interest in educational television stemmed from her deeper passion for educational equality. After participating in Operation Headstart, a federal program launched in 1965 aimed at providing early childhood education for low-income children, she saw a greater need for high-quality kindergarten instruction.

“In many poverty[-stricken] homes children haven’t even seen books or heard good music. But even in middle or upper class homes, children of working parents often lack opportunities… the parents just don’t have time,” the television teacher elaborated to the St. Petersburg Times.

Determined to help bridge the gaps, Nancy Benda pitched a new children’s television show to WFSU-TV.

“Miss Nancy’s Store”

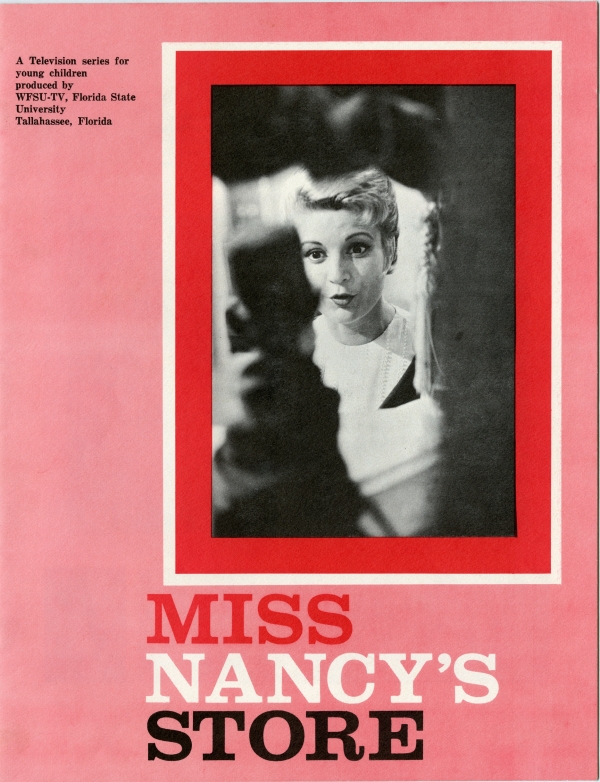

In 1965, the Florida Department of Education partnered with WFSU-TV to create, “Miss Nancy’s Store,” an enchanting new after school puppet show geared toward boosting childhood literacy. The series starred Benda in the title role and premiered in January 1966.

At the height of its run, “Miss Nancy’s Store” aired on all six public television stations in Florida five nights per week at 5:00 p.m, with a potential viewing audience of six million people.

“It’s really a cooperative venture. Parents in the community have felt a need for a children’s show in the area at this time–something they could be sure wouldn’t have to be supervised, something educational, sound, well-done and enjoyable,” she explained.

While filming the show, Benda also earned her master’s in elementary education supervision via correspondence graduate courses at FSU. She brought her expertise to the set and hit all the right marks with viewers.

Miss Nancy stands next to a magical pot-bellied stove in her store, ca. 1966. On the show, the stove’s smoke transported children into an alternative world filled with music and moving pictures. Other props included a “no-cracker cracker barrel” filled with toys, a gramophone, and a secret door in the brick wall where puppets appeared.

Upon turning on the tube, children were transported in the magical world of Miss Nancy’s Store. To get youngsters excited about learning, Nancy employed creative tactics not feasible in a regular classroom. Miss Nancy played dress up and taught language lessons with the help of the show’s colorful puppet characters. “We want children to watch because [they are] interested, not because mama or teacher says it’s good to learn,” she emphasized to a reporter.

Booklet detailing the different characters and quirks of “Miss Nancy’s Store,” as well as the information about the show’s current and future budget, 1966. Nancy Benda Collection (N2016-1), Box 05, Folder 9, State Archives of Florida. Click to enlarge and flip through the full record.

“Miss Nancy’s Store” ranked number one on WFSU-TV’s Channel 11, receiving 11,000 pieces of fan mail in its first year. To make the show more interactive, she spent the last few minutes of each episode acknowledging viewers’ birthdays and reading fan letters. Florida Commissioner of Education Floyd T. Christian praised the show for its top-notch instructional content.

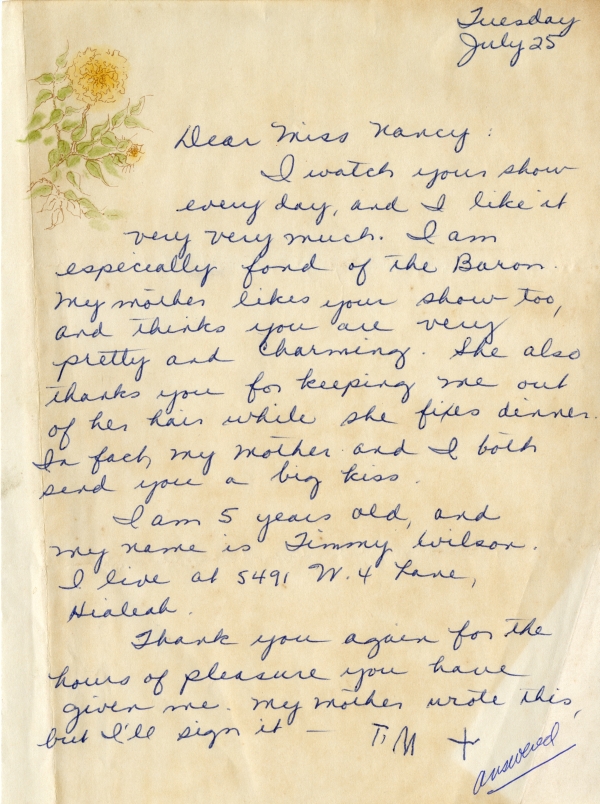

“I watch your show every day, and I like it very very much…. My mother likes your show too, and thinks you are very pretty and charming. She also thanks you for keeping me out of her hair while she fixes dinner. [We] both send you a big kiss,” gushed one young viewer.

Fan letter to Nancy Benda from five-year-old Timmy Wilson of Hialeah, ca. 1966. Nancy Benda Collection (N2016-1), Box 05, Folder 10, State Archives of Florida.

Despite such favorable ratings and reviews, the show billed high production costs. And a lack of funding forced the network to cancel “Miss Nancy’s Store” in August 1967. Fans, from kindergartners to grandparents, wrote futile pleas to the show’s producers, begging them to keep it on the air.

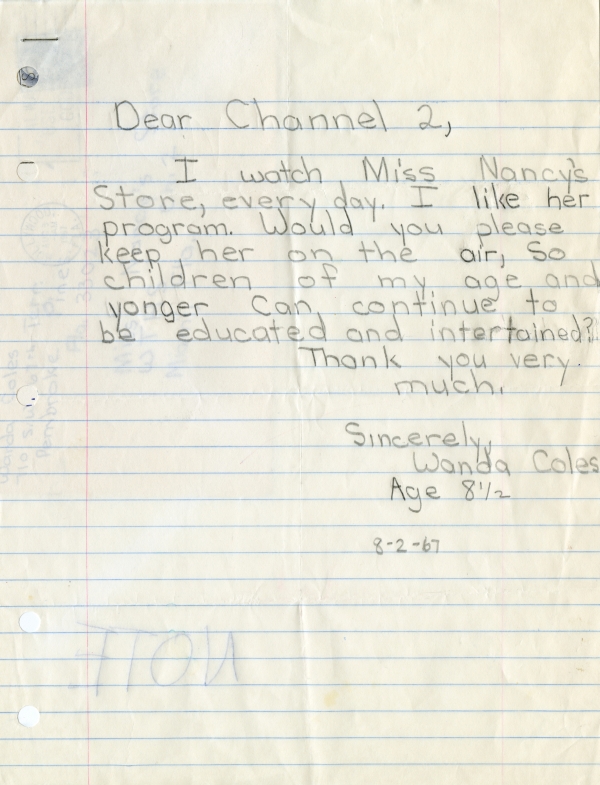

“I watch Miss Nancy’s Store, everyday. I like her program. Would you please keep her on the air, so children of my age and yonger [sic.] can continue to be educated and intertained [sic.]?”

Letter from “Miss Nancy’s Store” fan Wanda Coles in reaction to series cancellation, August 2, 1967. Nancy Benda Collection (N2016-1), Box 05, Folder 12, State Archives of Florida.

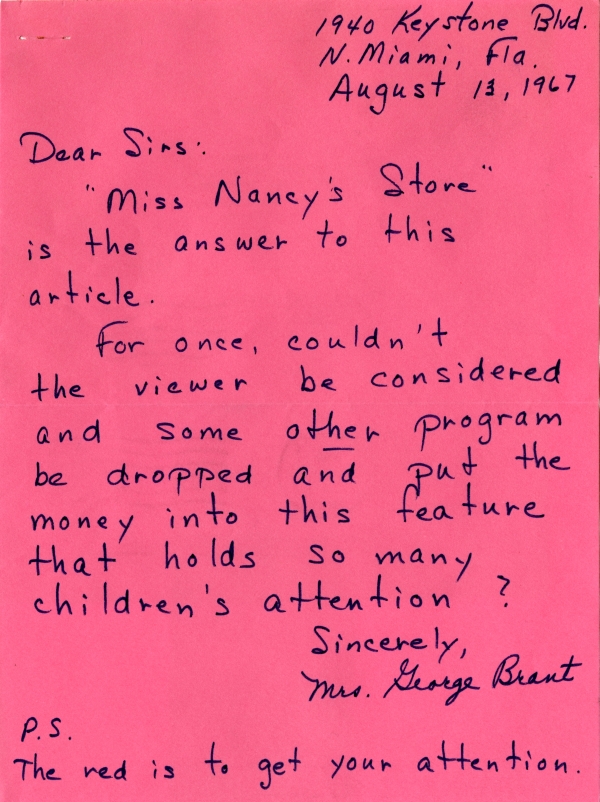

One adult viewer pleaded with producers to keep the show on the air, asking if “For once, couldn’t the viewer be considered and some other program be dropped and put the money into this feature that holds so many children’s attention?” She attached an article referring to children’s TV as a “mini-wasteland” to support her case.

Letter to WFSU-TV producers from Mrs. George Brant on the cancellation of “Miss Nancy’s Store,” August 13, 1967. Nancy Benda Collection (N2016-1), Box 05, Folder 12, State Archives of Florida. Click to view full record.

Lifelong Educator

Once “Miss Nancy’s Store” stopped filming, Benda accepted a job with the Florida Department of Education (FDOE) as the director of equal opportunity programs. Until her retirement in 2003, the former television star took up the charge of enforcing Title IX–a 1972 federal law barring sex discrimination in scholastic and athletic programs at educational institutions receiving federal funds–in Florida’s public schools. She traveled the state investigating the disparities in athletic offerings for male and female students. Sports teach discipline and competition, she said. Benda intimated that “those are skills that have served our males very well,” and would benefit women as well.

In 1993 she traveled to Washington D.C., testifying as a witness in a congressional hearing on alleged sex discrimination in secondary and collegiate level sports. Toward the end of her tenure with FDOE, Benda expressed tempered views on the progress of educational opportunity in Florida: “Schools have made some enormous strides, [but] there’s a lot of work to be done.”

Nancy Tribble Benda died of cancer in 2015 at the age of 85. After the former educator’s passing, her family donated her career files to the State Archives of Florida for preservation. The collection documents the television teacher’s historic contributions to expanding educational access in Florida.

Florida now boasts a total of 13 public access channels, their success owed in part to the educational television framework built by innovative teachers like Nancy Benda.

Selected Sources:

Nancy Tribble Benda Collection (N2016-1). State Archives of Florida.

Educational Television Commission Minutes (.S 1913). State Archives of Florida.

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "Miss Nancy's Story." Floridiana, 2017. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/332712.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "Miss Nancy's Story." Floridiana, 2017, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/332712. Accessed December 27, 2024.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2017, June 6). Miss Nancy's Story. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/332712

Listen: The FolkFolk Program

Listen: The FolkFolk Program