Description of previous item

Description of next item

Migrant Education Programs in Florida

Published November 11, 2017 by Florida Memory

The years spent in elementary school are formative ones in a child’s upbringing. But what if a child must move several times per year due to their parents’ work demands? In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Florida’s educators initiated compensatory education programming to benefit the children of migrant workers, whose frequent moves due to shifting employment circumstances posed difficulties for their social and educational gains.

In an August 1971 issue of Young Children (the journal of the National Association for the Education of Young Children), Eloyce Combs, early childhood education consultant for the Florida Department of Education, outlined the problem of education for migratory children: “Because of the mobility of migrant families,” Combs wrote, “the young children often suffer from… lack of medical and dental services, limited educational experiences… [and] must struggle with the major crises of development[,] such as the requirement to tolerate separation from the mother, [and] to find new friends when the family has to move.”

Mobile instruction units arrive at migrant labor camp in Broward County, ca. 1970. Found in series S 944, box 14, folder 30.

In supplying access to low-cost produce, the labor of migrant farm workers has sustained Floridians’ nutritional and financial needs for much of the state’s history. However, not until the late 1960s, in the wake of President Lyndon Johnson’s anti-poverty legislation, did federal and state governments began to address the specialized educational and social development needs of migratory children.

Records from Series S 944, Florida Migratory Child Compensatory Program Files, 1967-1974, illustrate initiatives on the part of educators, politicians and activists to improve access to healthcare and higher quality education for migratory children.

Lyndon Johnson Signs the ESEA

During the Great Depression, a young Lyndon Johnson taught the children of migrant workers in the Rio Grande Valley in Texas. The child poverty that he witnessed during his time as a schoolteacher would influence his later directives as president. Following the signing of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, Johnson began to prioritize poverty as a domestic policy issue. In 1965, Johnson signed the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) of 1965, granting federal funding to programs designed to close the skills gap in math, reading and writing for schoolchildren from low-income urban and rural households.

Early Childhood Learning Programs for Migrant Children in Florida

One program to receive federal funding under the ESEA was the Florida Migratory Child Compensatory Program, administered by the Florida Department of Education. At its inception in 1967, the program offered special education programming to provide for the needs of migratory farm workers in 20 Florida counties. Beginning in 1967, county school boards applied for ESEA grants on an annual basis to provide migratory students with textbooks, remedial math and language arts coursework, field trips, home visitation programs, summer school programs and in-service training for their teachers and other school staff.

Remedial language arts class administered through the Migratory Child Compensatory Program, ca. 1970. Found in series S 944, box 14, folder 57.

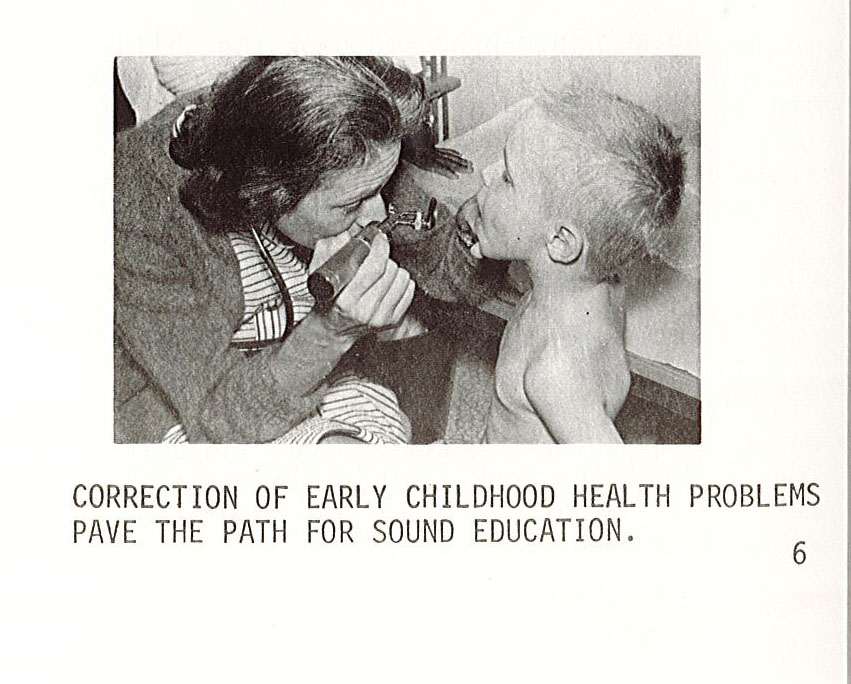

County grant applications often also requested supplemental funding to address migratory students’ health care needs, such as testing for hearing and visual impairment and psychological testing to identify special education needs, and for the provision of essentials such as food, clothing and glasses.

Child receives health services provided through Migrant Education Center in Broward County, 1971. Image excerpted from 1971 issue of The Traveler, the newsletter of the Broward County Migrant Education Center. Found in series S 944, box 14, folder 61.

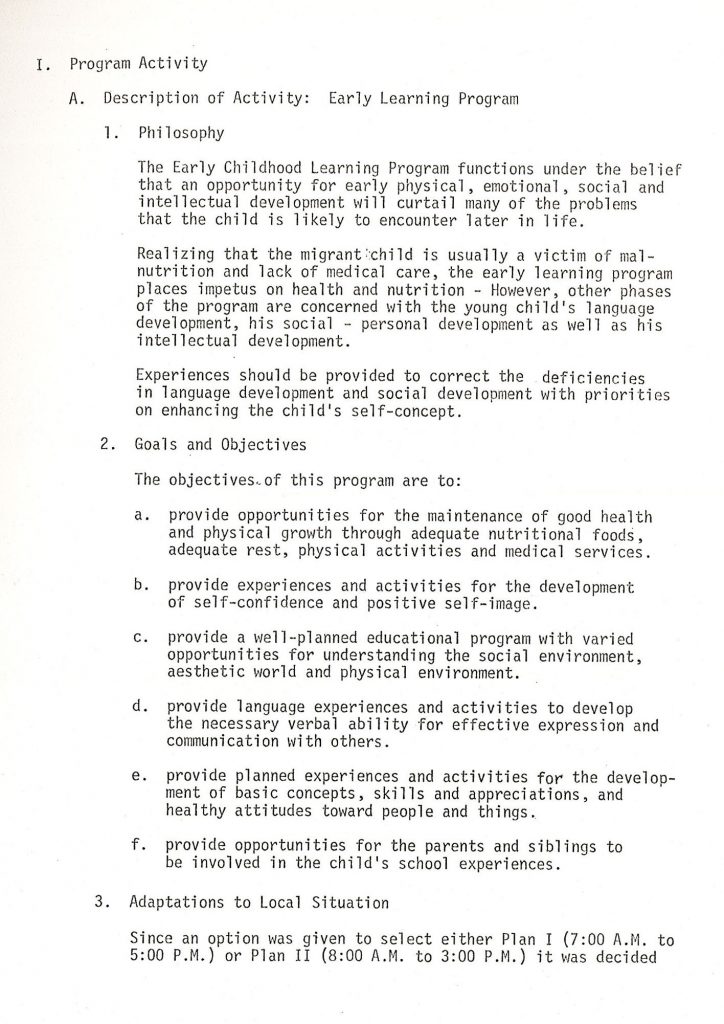

County school boards designed their programs to correct “deficiencies in language development and social development with priorities on enhancing the child’s self-concept” and to “provide experiences and activities for the development of self-confidence and positive self-image” of their students.

Excerpt from Broward County Migrant Education Program Year End Report, 1972-1973 school year. Found in series S 944, box 7, binder 3.

Such enrichment activities included field trips to petting zoos and meetings with Santa Claus.

Migratory school children meet with Santa Claus, St. John’s County. Found in series S 944, box 14, folder 47.

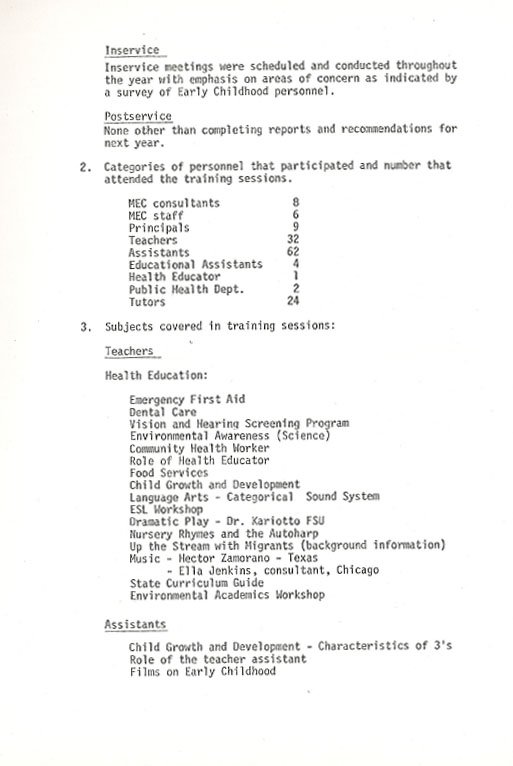

The efficacy of these migratory education initiatives in Broward County was evaluated by the Broward County Board of Public Instruction through standardized testing of students to measure gains in areas such as reading comprehension and vocabulary. Program effectiveness was also gauged by the number of instances of health and supportive services provided to students, as well as number of staff members receiving in-service training.

Three years after the program’s initiation, the results of the Migratory Child Compensatory Program were mixed. In an April 5, 1970, article from the Miami Herald, Mary Dorsey, an education specialist at the Migrant Education Center in Broward County, identified a need for more in-service teacher training and attributed low student test scores to lack of individualized help due to overcrowding and lack of materials. While Dorsey reported individual gains in reading ability among students, test scores in 1970 charted Broward County student achievement levels as remaining below the national average for the seventh consecutive year.

Excerpt from Broward County Migrant Education Program Year End Report (1972-1973) describing in-service teaching programs. Found in series S 944, box 7, binder 3.

Another critique of the program, and one possible explanation for its low impact on standardized test scores at the time, was a lack of bilingual programming.

In January of 1971, the Polk County school system held a forum to allow groups representing local educators, agricultural companies, ministries and migrant laborers to publicly discuss issues surrounding the county’s migrant education program–the largest in the nation at the time, instructing 6,500 migratory students that year. Those representing migrant laborers, such as the Florida Farmworkers’ Association, Polk County Christian Migrant Ministry and the Organized Migrants in Community Action criticized the government’s efforts in education for failing to tackle the barriers standing between monolingual English speaking teachers and their multilingual pupils. Though compensatory programs in Florida provided for teachers’ in-service training in areas ranging from remedial math courses to first aid to auto harp instruction, bilingual lesson instruction was not a standard feature of the programs.

The ESEA has been reauthorized by presidential authority once every five years since its inception. In 2001, the Act was reauthorized under President George W. Bush as the “No Child Left Behind Act,” and in 2015, President Barack Obama reauthorized the Act as the “Every Student Succeeds Act,” known as ESSA. The Migrant Education Program stills exists today in Florida under Title I, Part C of ESEA. In accordance with revisions to the ESEA, the program is assessed once every five years and modified to conform to regulations at the federal level. It continues to allocate funding to schools with migratory student populations to support and advocate for migratory families and provide school placement assistance for migratory children.

Entrance to South Dade Farm Labor Camp, Homestead, ca. 1970. Found in series S 944, box 14, folder 56.

Behind every meal comprised of fresh Florida fruits and vegetables, there is a story of the difficult work that brought that meal to the consumer’s table. For researchers examining the intersections of labor trends and the economy, public health, education or social welfare, the experience of migrant worker offers an interesting lens.

Researchers with an interest in migrant labor in Florida will find the following series of use in their studies:

Series S 401 Migrant Labor Program Reading Files, 1970-1978

Series S 568 Migrant Labor Program Subject Files, 1970-1978

Series S 1172 Migrant Labor Program Administrative Files, 1973-1991

Series S 579 Migrant Health Program Administrative Files, 1972-1978

Sources:

Brucken, G. “Low Rank in Reading May Stay.” The Miami Herald, April 5, 1970.

Combs, E. “Florida’s Early Childhood Learning Program for Migrant Children.” National Association for the Education of Young Children, V (XXVI, 1971): 359-363.

McKee, G. A. “Lyndon B. Johnson and the War On Poverty.” Accessed October 24, 2017. http://prde.upress.virginia.edu/content/WarOnPoverty

Riley, N. Floridas farmworkers in the twenty-first century. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2002.

Roderus, F. “Many Groups Study Migrant Problem In Polk.” The Tampa Tribune, January 15, 1971.

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "Migrant Education Programs in Florida." Floridiana, 2017. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/332821.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "Migrant Education Programs in Florida." Floridiana, 2017, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/332821. Accessed December 28, 2024.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2017, November 11). Migrant Education Programs in Florida. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/332821

Listen: The World Program

Listen: The World Program