Description of previous item

Description of next item

Congress of Racial Equality (CORE)

Published February 2, 2018 by Florida Memory

In the summer of 1959, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) organized the Miami Interracial Action Institute and taught attendees principles of non-violent direct action to combat inequality in the South. Two attendees, sisters Patricia and Priscilla Stephens, took these principles with them when they returned to Tallahassee for school and formed the Tallahassee chapter of CORE. Using tactics they learned at the CORE workshop, the Stephens sisters held their first sit-in at the Woolworth’s lunch counter in Tallahassee on February 13, 1960, and a second sit-in at the same lunch counter a week later, which led to the arrest of the sisters and a group of other students. Rather than pay their fines, eight students opted for jail time in one of the first jail-ins of the civil rights movement.

The eight jailed students and CORE were suddenly thrown into the national spotlight. CORE used the opportunity to draw attention to their organization. What were CORE’s principles, and how could people join the growing civil rights movement through CORE? Using records from the Patricia Stephens Due Papers (N2015-1), we take a look at the materials CORE published and how young activists in Florida, including the Stephens sisters, used CORE as the foundation for fighting racial discrimination.

Participants in the CORE Miami Interracial Action Institute in 1959 at the Sir John Hotel. Seated, left to right: Mrs. Shirley Zoloth, Patricia Stephens (later Due), person unknown, Vera Williams and Priscilla Stephens (later Kruize). Standing, left to right: Jim Dewar, Zev Aelony, person unknown, James T. McCain and Gordon Carey.

CORE formed its Miami chapter in 1959 and the Tallahassee chapter emerged soon after. By the time the organization made its way to Florida, CORE had been active in the United States for nearly two decades. Started in 1942 by pacifist students at the University of Chicago, CORE’s members wanted to use Gandhian techniques of non-violent direct action to improve race relations in the United States. CORE grew out of another pacifist organization, the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), which was started during World War II with a focus on non-violent direct action for social justice. The first course of action for CORE was to counter the discriminatory housing market in the Chicago area, but their activism quickly grew to a national scale when CORE members decided to target bus segregation in the South.

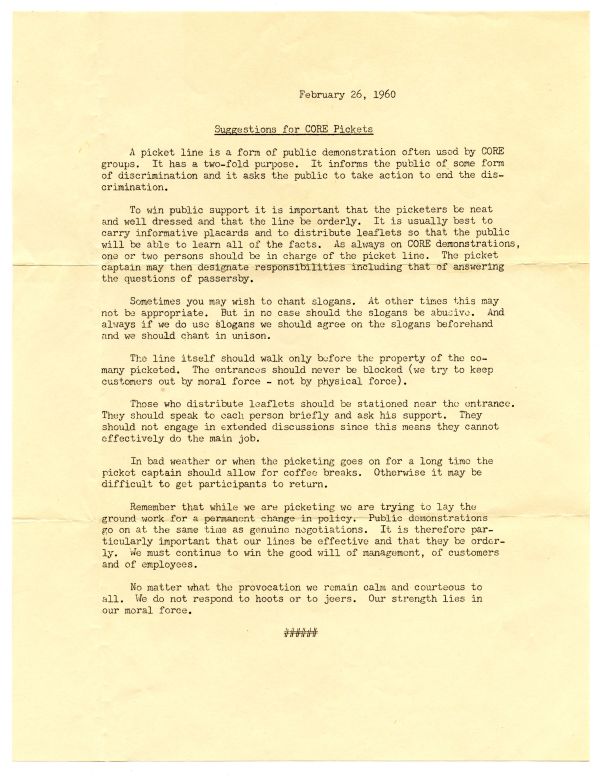

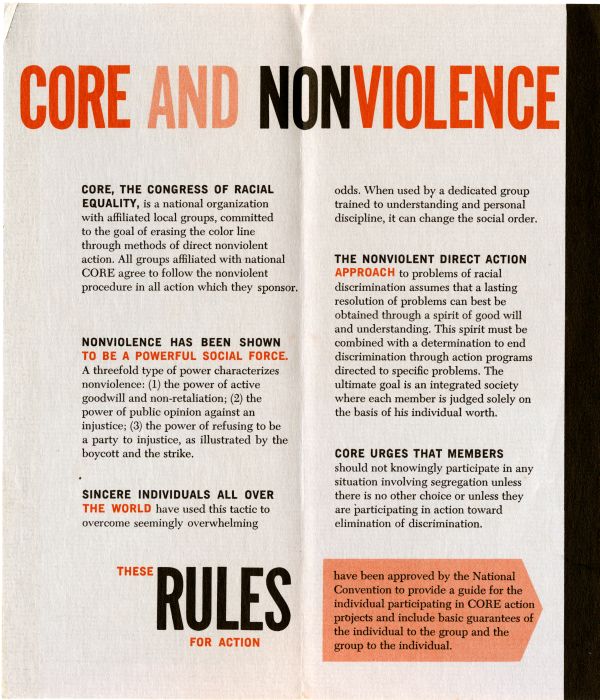

A pamphlet about CORE’s principles of non-violent direct action which includes 13 rules for action, ca. 1957.

In April 1947, 16 male CORE and FOR members began a project called the “Journey of Reconciliation” through Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee and Kentucky to test integration on interstate buses. The eight black and eight white activists were responding to the recent U.S. Supreme Court decision in Irene Morgan v. Commonwealth of Virginia (1946), which ruled segregation in interstate bus travel unconstitutional. With the law on their side, the 16 men rode buses and trains across these Southern states. Some were arrested, but others were able to ride public transportation without any attention. When a rider was confronted, he would use the non-violent tactics he had learned and cite the Supreme Court decision. Although this protest against bus segregation received little national press coverage at the time and resulted in almost no changes to discriminatory policies, it paved the way for the Freedom Rides in 1961.

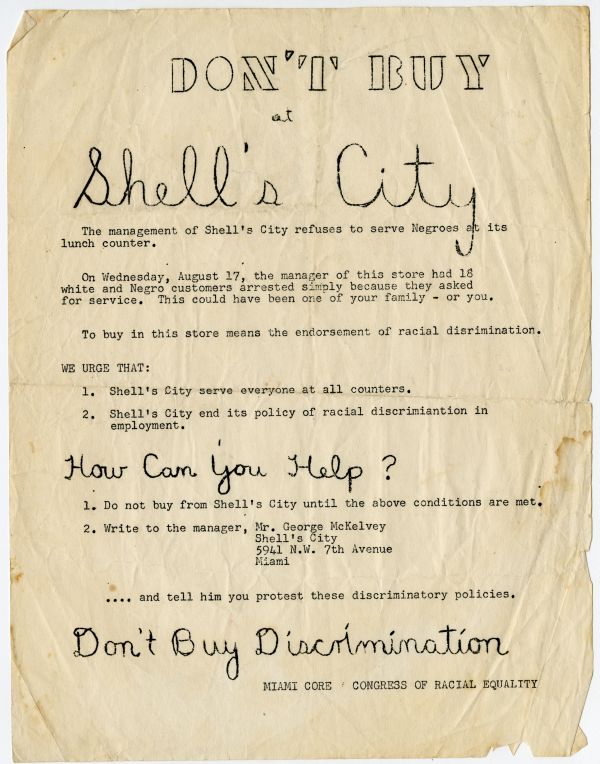

A CORE flier encouraging people to boycott Shell’s City in Miami for refusing to serve African-Americans at its lunch counter, ca. 1960.

In the mid-1950s, CORE slowly began to establish chapters throughout the country. After the first all-white school in Miami was integrated in 1959, CORE headed to this southern city and started a chapter. CORE then decided to host the Interracial Action Institute, which the Stephens sisters and 10 others from all over the U.S. attended. One of the purposes of the institute was to train participants to use non-violent direct action “as a weapon to advance integration.” Since CORE couldn’t be everywhere at once, their goal was to train people locally so they could then use CORE tactics in their communities. At the institute, participants went through intensive training by role-playing different scenarios they might encounter while holding their demonstrations and were taught how to respond. Participants then put theory into practice, leading a voter registration drive by going door to door in black communities and holding lunch counters sit-ins to challenge discriminatory policies under the guidance of CORE leaders. When the workshop was over, participants went back to their homes to carry on the fight for equality.

The Stephens sisters returned to Tallahassee for the fall semester at Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University (FAMU) ready to challenge discrimination in the capital city. They quickly formed a CORE chapter in Tallahassee and began documenting instances of discriminatory policies. The February 1, 1960, lunch counter demonstration at the Woolworth store in Greensboro, North Carolina, laid the groundwork for sit-ins across the South. Inspired by the non-violent direct action demonstration of the four students in Greensboro, national CORE asked local chapters to hold sympathy demonstrations in their communities. Ten students, including the Stephens sisters, participated in a sympathy sit-in at Woolworth’s lunch counter in Tallahassee on February 13. The students ordered slices of cake and were refused service. During their two hours at the lunch counter, the students were derided by onlookers, but they remained faithful to their CORE training and didn’t engage with the crowd. When Woolworth’s management closed the counter, the students went home.

CORE members holding a sit-in at Woolworth’s lunch counter on February 13, 1960. Patricia Stephens is wearing dark glasses and Henry Steele Jr. sits closest to the camera.

After this first sit-in, Tallahassee CORE planned another for the following Saturday. On February 20, a group of 17 demonstrators made their way to the Woolworth’s lunch counter and ordered food. Most of the group was composed of FAMU students, but there were also high school students participating. A large group surrounded the demonstrators and told them to move from their seats. Seven of them did leave, but the 11 remaining demonstrators were arrested by police. At their trial, they were charged with disturbing the peace. All of them were found guilty and given the option to pay a $300 fine or spend 60 days in jail. Eight students, including the Stephens sisters, refused to pay the fine. Rather than pay, they chose to hold one of the first jail-ins of the civil rights movement. As a result, CORE and its principles of non-violent direct action were placed in the national spotlight, and people from all over the country wrote to the jailed students to offer support for their demonstrations. When the students were released from jail after serving 49 days, they persistently pursued racial equality in the United States.

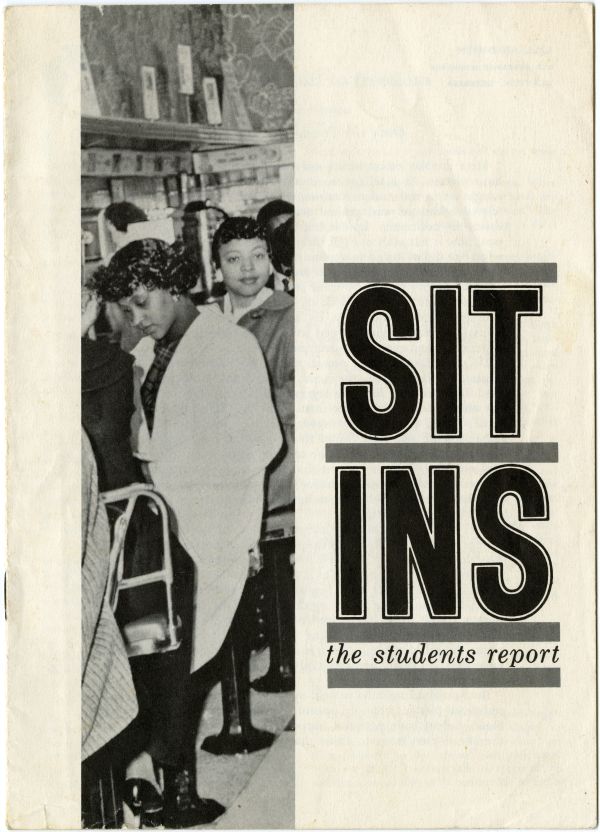

A booklet published by CORE consisting of six stories written by young people involved with sit-ins and other non-violent demonstrations across the United States, May 1960. Patricia Stephens tells her story from jail where she was serving her 60-day sentence with seven other activists, including her sister, Priscilla. Patricia writes about the events leading up to being jailed and the conditions at the Leon County Jail in Tallahassee. The other five stories were written by Edward Rodman (Portsmouth, Virginia), Paul Laprad (Nashville, Tennessee), Thomas Gaither (Orangeburg, South Carolina), Major Johns (Baton Rouge, Louisiana) and Martin Smolin (activities in the North).

Activists continued to use the principles of CORE throughout the civil rights movement. Financial problems and internal disputes, which plagued CORE from the beginning, led to the collapse of many local chapters by the mid-1960s. Now CORE is remembered as one of the leading organizations during the fight for civil rights and as the catalyst for civil rights activities in Florida.

You can learn more about the Tallahassee jail-in in our online collection, Stephens Sisters Jail-In Papers, 1960.

Resources

Catsam, Derek Charles. Freedom’s Main Line: The Journey of Reconciliation and the Freedom Rides. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2009.

Due, Tananarive, and Patricia Stephens Due. Freedom in the Family: A Mother-Daughter Memoir of the Fight for Civil Rights. New York: Ballantine Books, 2003.

Gates, Jr., Henry Louis. Life Upon These Shores: Looking at African American History 1513-2008. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2011.

Meier, August, and Elliott Rudwick. CORE: A Study in the Civil Rights Movement 1942-1968. New York: Oxford University Press, 1973.

Mohl, Raymond A. South of the South: Jewish Activists and the Civil Rights Movement in Miami, 1945-1960. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2004.

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "Congress of Racial Equality (CORE)." Floridiana, 2018. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/332827.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "Congress of Racial Equality (CORE)." Floridiana, 2018, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/332827. Accessed December 27, 2024.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2018, February 2). Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/332827

Listen: The Blues Program

Listen: The Blues Program