Description of previous item

Description of next item

Conscripting Confederates in Florida

Published May 5, 2013 by Florida Memory

The Confederate government instituted few policies that were more controversial than conscription. Initially passed on April 16, 1862, the first of three conscription acts required that all able-bodied white males between the ages of 18 and 35 serve in the Confederate military forces for three years or until the end of the war. The unprecedented nature of conscription—there had never been a national draft in America before 1862—roused public debate about its necessity and constitutionality. Most Southerners hated conscription. They believed it demeaned patriotism by pressuring men to serve instead of relying on their willingness to volunteer. Even more demeaning were the exemptions to the act, which allowed the wealthy to avoid conscription by hiring substitutes and kept those employed in professions deemed essential for the operation of the economy and government out of military service.

One of the most resented of these exemptions was a provision in the second Conscription Act (October 1862) that exempted planters who owned twenty or more slaves from the draft. The exemption also applied to overseers employed in managing plantations with over twenty slaves. Soon known among the press and public as the "Twenty Negro Law," the exemption provoked outrage among poor and middle class whites, most of whom owned no slaves or certainly fewer than the twenty slaves required by the law.

Poor and middle class Floridians opposed the exemption as vehemently as other Southerners. A conscription officer reported to Governor John Milton that "opposition to the conscription act so far as regards the particular exemption of all owning twenty or more slaves, is widespread and I fear universal. I have been told that many swear that they will not be taken as Conscripts while their wealthier neighbors are left in the enjoyment of home and its comforts."

Governor Milton reluctantly supported conscription as an evil necessary for military victory and opposed certain occupational exemptions which he believed were being abused by men to avoid military service. For example, the exemption for salt makers led to the influx of thousands of men into Florida who claimed to be salt makers but who were really just evading the draft. He was not as critical of exemptions that applied to his own planter class. Milton believed the "Twenty Negro Law" was required for security and productivity on plantations. He feared the absence of an owner or overseer would lead to slave rebellions and a drop in food production essential for the feeding of Floridians and their soldiers.

Public criticism of the "Twenty Negro Law" became so great, however, that on May 1, 1863, the Confederate Congress modified the hated exemption. From now on, the exemption for overseers would only apply to those plantations employing twenty or more slaves where the owner was either a minor, a single female, of unsound mind, or absent from home engaged in military service. In addition, the overseer had to have held his position before April 16, 1862, the date of the passage of the first Conscription Act.

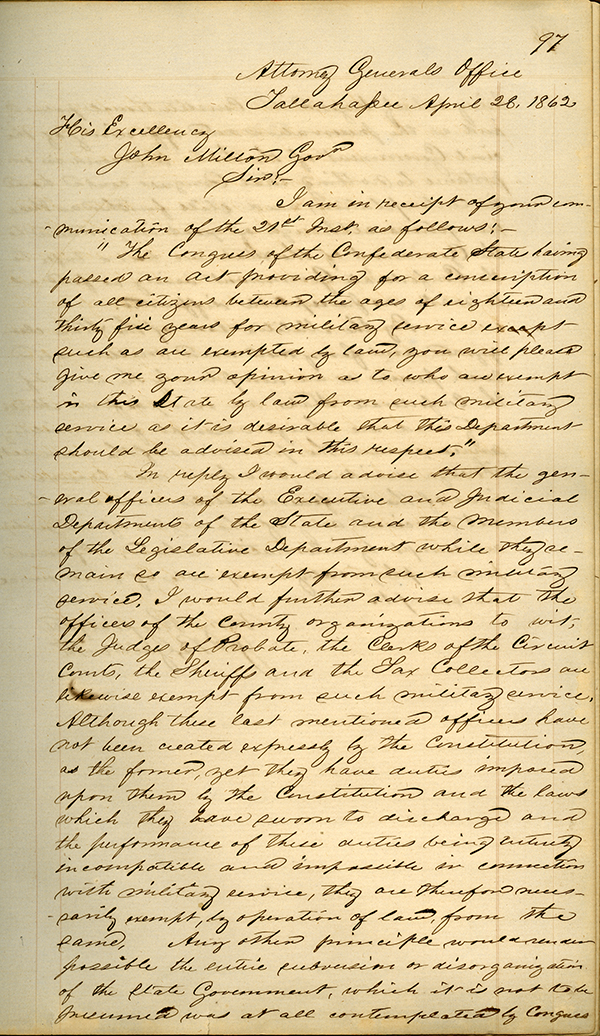

Letter from John B. Galbraith to John Milton, April 28, 1862. State Archives of Florida, Florida Attorney General Opinions, Series S632.

On May 29, after learning that his own overseer, John Parks, had dutifully reported for conscription, Milton sent letters of protest to both Confederate president Jefferson Davis and Howell Cobb, the area Confederate commander. Milton urged on President Davis the necessity of keeping overseers on plantations to maintain adequate food production. This was especially important in Florida, Milton pleaded, due to the fact that there were few able bodied males in the state older than 45, the upper age limit of conscripts by 1863, who could perform the arduous work of overseers once the younger overseers were conscripted. Milton asked General Cobb to release Parks from military service and exempt him from future conscription. Although Cobb was in agreement with Milton and quickly saw to Parks' release from military service, Davis upheld the new conscription law despite his appreciation for Milton and Florida's many sacrifices for the Confederate cause.

For more information, see Ridgeway Boyd Murphree, "Rebel Sovereigns: the Civil War Leadership of Governors John Milton of Florida and Joseph E. Brown of Georgia, 1861-1886" (Phd. dissertation, Florida State University, 2006). For a history of Confederate conscription see Albert Burton Moore, Conscription and Conflict in the Confederacy (New York: Macmillan Company, 1924).

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "Conscripting Confederates in Florida." Floridiana, 2013. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/259732.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "Conscripting Confederates in Florida." Floridiana, 2013, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/259732. Accessed December 28, 2024.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2013, May 5). Conscripting Confederates in Florida. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/259732

Listen: The Latin Program

Listen: The Latin Program