Description of previous item

Description of next item

The Tallahassee Bus Boycott

Published May 5, 2013 by Florida Memory

On May 26, 1956, two female students from Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University (FAMU), Wilhelmina Jakes and Carrie Patterson, sat down in the "whites only" section of a segregated bus in the city of Tallahassee. When they refused to move to the "colored" section at the rear of the bus, the driver pulled into a service station and called the police. Tallahassee police arrested Jakes and Patterson and charged them with "placing themselves in a position to incite a riot."

In the days immediately following these arrests, students at FAMU organized a campus-wide boycott of city buses. Their collective stand against segregation set an example that propelled like-minded Tallahassee citizens into action. Soon, news of the boycott spread throughout the community.

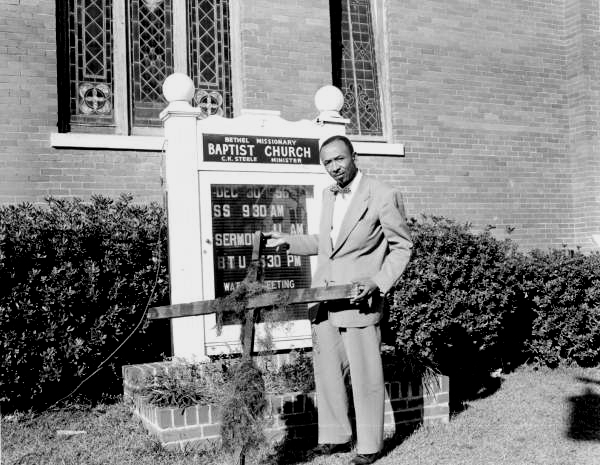

Reverend C.K. Steele orchestrated the formation of an organization known as the Inter-Civic Council (ICC) to manage the logistics behind the boycott. Steele and other leaders created the ICC because of unfounded negative publicity surrounding the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). The NAACP faced persistent attacks from segregationists who claimed that the organization was a front for communist activity. Despite the local origins of the boycott, segregationists seized upon the notion that outside agitators, meaning communists from the NAACP, intended to use the case of Jakes and Patterson to inflame racial tensions in Tallahassee.

The ICC devised a car pool system to provide transportation for African Americans during the boycott. City officials quickly charged ICC leaders with operating an illegal for-hire operation without a franchise. Reverend Steele was among those later arrested in connection with the car pools. The slogan for the movement, attributed to Steele, became "I would rather walk in dignity than ride in humiliation."

As the boycott dragged on into the summer, the Tallahassee police continually harassed its organizers as well as rank-and-file members of the ICC, many of whom were FAMU students. Segregationists smashed windows at Reverend Steele's house and burned crosses on numerous occasions in an attempt to intimidate the African-American community.

The legislature, concerned that the example of Tallahassee would spread beyond the capital city, initiated investigations of civil rights organizations and leaders under the auspices of the Florida Legislative Investigation Committee (FLIC), also known as the Johns Committee. The FLIC maintained extensive files on organizations such as the ICC and the NAACP but paid little more than lip service to curtailing violence committed by white terrorist groups such as the Ku Klux Klan (KKK). Many historians believe that the sole purpose of the Johns Committee was to manufacture links between the Civil Rights Movement and an imagined international communist conspiracy. Indeed, the FLIC became the Florida manifestation of McCarthyism. However, this witch hunt took on the decidedly Jim Crow era southern angle of both anti-communism and anti-integration.

Seth Gaines with his taxi in Tallahassee, ca. 1950. Gaines drove an independent taxi in the 1940s and 1950s. In response to demands from civil rights activists during the 1956-57 bus boycott, he became the first African American person to drive buses on a regular route for the Cities Transit Company in Tallahassee.

The strategy of the ICC had an immediate impact on bus fare revenues. On July 1, Cities Transit, the company that operated the Tallahassee bus franchise, announced that it was forced to suspend all routes because of the financial impact of the boycott. The ICC won its first major victory in early August when Cities Transit announced that the company would resume service and hire African-American drivers on the predominately black FAMU and Frenchtown routes.

On October 21, as the boycott entered its fifth month, Tallahassee judge John A. Rudd convicted 21 ICC members of operating a transportation business without a franchise approved by the city. Jail sentences for the car poolers were suspended, but the court levied $11,000 in fines against the ICC. Reverend Steele traveled extensively at this time, garnering support for the Tallahassee movement and raising funds to pay fines and legal fees.

The Tallahassee Bus Boycott received a boost when, in December 1956, the U.S. Supreme Court issued its ruling in a case that originated from the Montgomery Bus Boycott. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Alabama's segregated busing laws were unconstitutional. Shortly thereafter, the court ordered Alabama to desegregate its public buses.

ICC leaders in Tallahassee decided to test whether the U.S. Supreme Court decision would be enforced in Florida. In late December 1956, Steele and several other prominent Tallahassee civil rights leaders, including Reverend Daniel Speed, boarded segregated buses and sat in seats reserved for whites without incident. Larger "front ride" demonstrations were called off when armed whites threatened to confront the integrationists.

Reverend C. K. Steele (left) and Reverend Dan Speed protesting segregated busing, Tallahassee, December 24, 1956

In the midst of growing pressure from all sides, Governor LeRoy Collins suspended all bus service in Tallahassee as of January 1, 1957. Days later, on January 7, the city repealed the segregated seating ordinance, citing the recent federal ruling in the Montgomery case. The city then enacted an "assigned seating" ordinance that, while not violating the decision by the high court, maintained a measure of segregated seating to ensure "maximum health and safety" for the public.

By the summer of 1957, all city buses in Tallahassee were fully integrated. According to Tallahassee historians Mary Louise Ellis and William Warren Rogers, "City commissioners and protesting blacks never achieved a formal settlement, but gradually the sight of blacks riding at the front of the bus became more common, and the battle moved to another front."

Through courageous nonviolent protest, boycotters in Tallahassee achieved an important victory in the struggle for civil rights. The case of Tallahassee proved that Montgomery was not an anomaly and that a commitment to nonviolence could achieve significant results towards equality.

Cite This Article

Chicago Manual of Style

(17th Edition)Florida Memory. "The Tallahassee Bus Boycott." Floridiana, 2013. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/259734.

MLA

(9th Edition)Florida Memory. "The Tallahassee Bus Boycott." Floridiana, 2013, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/259734. Accessed December 27, 2024.

APA

(7th Edition)Florida Memory. (2013, May 5). The Tallahassee Bus Boycott. Floridiana. Retrieved from https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/259734

Listen: The Blues Program

Listen: The Blues Program