Distant Storm: Florida's Role in the Civil War

A Sesquicentennial Exhibit

Florida’s Role in the Civil War

Before 1861: Florida’s Journey into Civil War

Slavery in Florida, 1821 to 1861, and the Business of Cotton

The immediate impetus for Florida’s movement towards secession and civil war was the election of Abraham Lincoln to the presidency of the United States on November 6, 1860.

While slavery remained an important component of the economy of the old Spanish settlement areas in East Florida up to the Civil War, the focus of plantation slavery in Florida shifted to Middle Florida soon after the United States acquired the territory and made Tallahassee, in Leon County, the capital.

Consisting of the counties from the Apalachicola to Suwannee Rivers, but including Jackson County to the west of the Apalachicola, Middle Florida was the political and economic core of antebellum Florida. By 1830 these counties hosted most of the territory’s population and had more slaves than white citizens.

Most Middle Florida plantations produced food crops, but a planter’s way to riches meant the ability to acquire land. And the quickest way to acquire the capital for land was to sell cotton, the region’s most lucrative cash crop. As early as 1828, the port of Apalachicola shipped 55,000 bales. By 1840, 80 percent of Florida’s cotton crop was being harvested in Middle Florida.

The growth of the cotton business encouraged immigration to Florida. Planters, merchants, craftsmen and small farmers moved to the territory in pursuit of their fortunes. Although the vast majority of these settlers were from the South, Northerners also formed part of the migration.

One of these Northern settlers was Daniel H. Wiggins, a native of New York and resident of Annapolis, Maryland, who moved to Florida in 1838. A millwright and inventor, Wiggins hoped to build and sell his design for a cotton press. Wiggins settled in Jefferson County and often did work for Thomas Randall, a fellow Marylander who owned two plantations in the county.

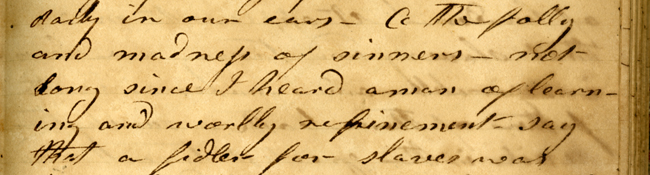

During his time in Florida, Wiggins kept a diary and recorded his observations about plantation life, including cotton production, slave manners and the often brutal punishments slaves received at the hands of masters and overseers. A devoutly religious man, Wiggins routinely interspersed his observations with religious references, especially when it came to slavery.

Wiggins seems to have abhorred the institution and believed that slaves should receive religious instruction, which he was allowed to give them. However, he, like most white people of his day, believed slaves to be racially inferior, childlike beings, who needed constant supervision and discipline. The following passages from the diary (June 30, 1839, and January 31, 1841,) reflect his ambivalence about slavery.

Daniel Wiggins’ observations on slavery in Jefferson County

(M89-32, Daniel H. Wiggins Diaries, 1816-1834, 1838-1841, and 1862)

Text from diary:

CC (Concerning) the folly and madness of sinners—not long since I heard a man of learning and refinement say that a fiddler for slaves was better than a minister. I was almost horror struck but did not feel at liberty to reprove – now that man is in his grave. We hold no meeting to day for the colored people, but I have appointed a meeting (the Lord wiling) to be held next Sabbath at 3 oclock under the shady trees by my shop. I feel an increasing desire for the salvation of the people. The soul of the slave is of as much value as the soul of the master—yet –? Neglected—too generally they are looked upon as mere beasts of burden—it appears to me that slavery and tirany are almost inseparable and ignorance is the father of them both—surely the devil is the greatest tirant and the greatest slave holder.

. . . . Last night after 12 oclock I woke up and heard the negroes dancing (as is often the case till nearly day on Sunday morn). I fell a sleep again and after a while was woken by the cry of a man as tho in great distress. At first I thought it was some one in liquor and was pretending to be under deep conviction from sin. I heard blows which I took to the sound of an axe—after a while the noise ceased for a moment—and then commenced again. I then discovered the blows to be the sound of a whip and the crying of the man occasioned by the whip. It appears that two strange negroes had come on this place and one without a pass, and the overseer was informed of it and caught them and he and his leader whipt one pretty severely—no doubt justly under existing circumstances they who are bound must obey.

The whipping of slaves and the requirement that they carry a pass outside of the boundaries of their masters’ plantations were part of the regime of slave codes that the legislatures of Florida and other slaveholding states passed to maintain control of their vast slave populations. Although these codes existed long before Nat Turner’s slave rebellion in Virginia in 1831, that event shocked the South, intensifying white fear of slave revolts. As a result, the work of slave patrols increased.

These groups of armed slave owners and white citizens patrolled the countryside at night to enforce the slave pass system and to break up any nocturnal slave gatherings. Just like many other white Southerners, many white Floridians believed Nat Turner’s rebellion was a prelude to a regionwide slave insurrection.

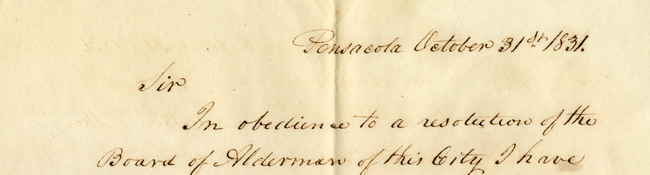

Mayor Peter Alba of Pensacola was so concerned about the Nat Turner revolt that he called for Florida’s territorial governor, William Duval, to ask for federal troops to be sent to Pensacola to guard against any possible slave rebellion.

Letter from Peter Alba, Mayor of Pensacola, to Sir [Governor DuVal], dated October 31, 1831, requesting troops to suppress an expected slave uprising. A resolution is attached.

Series 177, Territorial Governors’ Correspondence, 1820-1845

Pensacola October 31st 1831.

Sir

In obedience to a resolution of the Board of Alderman of the this City I have the honor to enclose to you a copy of a resolution of the Board requesting your earliest interposition with the Government to preserve the aid of some troops in this vicinity to repress the apprehended insurrection of people of color in this part of the Territory and neighboring State of Alabama.

I have the honor to be

Very respectfully

Your Obt. Servt.

Peter Alba

Mayor

Memorial sent to the War Dept

DuVal Signature

Resolved that the Governor of Florida be requested to make application to the General Government for one or two companies of Infantry to be stationed in or near Pensacola for the protection of the people of Florida against any insurrection of slaves or free negroes in the vicinity.

Board of Alderman of the City of Pensacola. October 31, 1831.

Extract from the minutes

Saml Fry

Secretary

The original sent to War Dept

Duval Signature

White Floridians realized their fears of slave rebellion in 1836, when Seminoles and their African allies launched a series of attacks on plantations in East Florida. These attacks came in the wake of the Seminole ambush of Major Francis Dade’s troops on December 28, 1835, an event known as the Dade Massacre, in which over 100 American soldiers died, sparking the Second Seminole War (1835-1842).

The slaveholders’ determination to quash slave rebellions and maintain slavery in the South was met by equally determined abolitionist sentiment from the North, where the anti-slavery movement was gaining strength by the time of Florida’s push for statehood in the early 1840s.

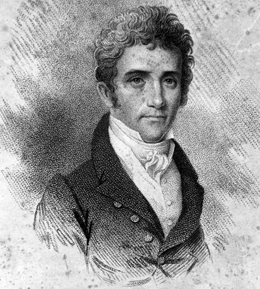

In June 1844, one such abolitionist, sailor and shipwright Jonathan Walker of Massachusetts, a former Pensacola resident who had left Florida because of his opposition to slavery, returned to Pensacola as captain of his own vessel. After arriving in port, Walker agreed to take aboard seven slaves who wanted to escape to freedom.

Walker and his party evaded the authorities in Pensacola and sailed east along the Gulf Coast to Apalachicola Bay. There the escape mission ended when Walker, incapacitated by sunstroke, could no longer pilot the vessel. A passing ship rescued Walker and his passengers and transported them to Key West, where they were jailed until returned to Pensacola in July 1844.

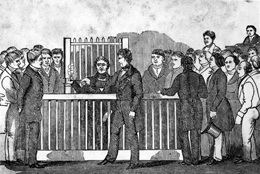

Imprisoned in Pensacola, Walker (the recaptured slaves were presumably returned to their owners) continued to suffer from sunstroke and general ill health as he awaited trial. He was eventually convicted of negro stealing, pilloried and pelted with rotten eggs, and then branded on his left hand with the letters SS for “Slave Stealer.”

After his release from prison in June 1845, almost a year after his original arrest, Walker devoted the rest of his life to the abolitionist cause, giving speeches across the North on the evils of slavery and drawing attention to his cause by displaying his branded hand.

On February 15, 1845, Governor John Branch sent a message to the legislature concerning the Walker case and attached a letter from the U.S. Marshal in Pensacola on Walker’s attempt to escape jail.

Branch’s message shows how seriously the South sought to defend the institution of slavery, and how it expected the federal government to uphold the constitutional right of a state to maintain slavery. His message and Marshal Eban Dorr’s letter also point to the South’s resentment of British anti-slavery efforts.

Correspondence Concerning Abolitionist Jonathan Walker

(Series 177, Territorial Governors’ Correspondence, 1820-1845)

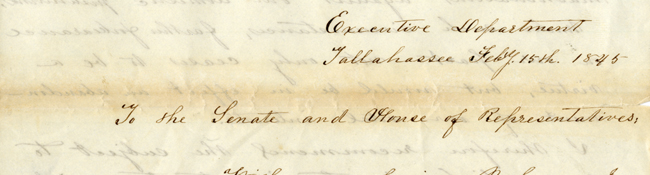

Executive Department

Tallahassee Febry. 15th 1845

To the Senate and House of Representatives,

With my opening message, I submitted a letter from the Secretary of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in relation to a certain Jonathan Walker convicted of stealing negroes, and who was then, and is now, confined in the Jail of Pensacola for said outrage; to which I again particularly invite your attention, in connection with the accompanying letters which I received by the last mail from the Marshal of the U. States for the Western District of Florida. From their perusal you will see that the “British and Foreign anti-slavery society for the abolition of slavery and the slave-trade throughout the world” has been clandestinely cooperating with the authorities of Massachusetts in fiendish machinations against our domestic institutions. “

Under such circumstances, farther forbearance on our part not only ceases to be a virtue, but would be in effect an abandonment of our vital interests. I therefore recommend the subject to your dispassionate investigation, with a decided opinion on my own part, that the time has arrived, when Florida has a right, nay would be false to herself were she not, to demand from the Federal Government a prompt enforcement of the guarantees of the Federal Constitution.

I have the honor to be,

Your Ob’t Sr.

Jn Branch

As the Original Letters are herewith sent, the Hon.b Senate will please transmit them to the House of Representatives after such orders shall be given, as are deemed necessary concerning them, together with this communication. Jn. B.

Correspondence Concerning Abolitionist Jonathan Walker (Series 177, Territorial Governors’ Correspondence, 1820-1845)

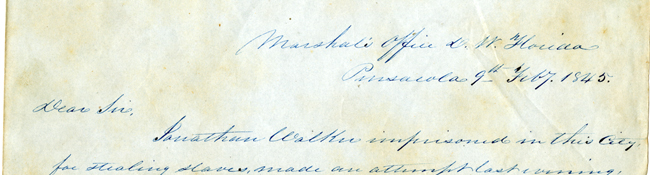

Marshal’s Office D. W. Florida

Pensacola 9th Febry. 1845

Marshall Office D. W. Florida

Pensacola 9th Feby. 1845.

Dear Sir,

Jonathan Walker imprisoned in the City

for stealing slaves, made an attempt last evening,

to break Jail, but was discovered before he could

make his escape, on his person was found the enc-

-losed communication from the British Foreign

Anti Slavery Society, which document might be viewed

by some of little importance, but to my mind taken

in connection with other facts, is further evidence

of the interference of a foreign power with our insti

-tutions, under the fictitious garb of Anti Slavery;

actuated by this impression, I transmit this

specimen of British vituperation to your Excellency

inspection.

I have the honor to be

Sir, very respectfully

Your Obt Servt

Eben Dorr

U. S. Marshal

D. W. F.

Correspondence Concerning Abolitionist Jonathan Walker

(Series 177, Territorial Governors’ Correspondence, 1820-1845)

His Excellency Gov. Branch

Tallahassee

#5

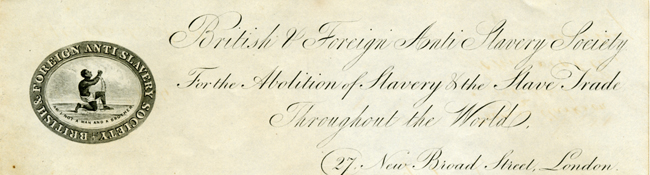

British & Foreign Anti Slavery Society

For the Abolition of Slavery & the Slave Trade

Throughout the World

27 New Broad Street, London

At a meeting of the Committee of the British and Foreign

Anti Slavery Society, held at No. 27 New Broad Street, on Friday Oct 6, 1844—

George Stacy Esq, in the Chair,

It was resolved Unanimously,

That considering the enormous wickedness of American Slavery,

whether viewed in relation to the iniquity of its principle, which deprives nearly

three millions of human beings of their personal rights; or to the atrocity of

its practice, which subjects them to the deepest degradation and misery; this

committee feel it to be their duty publicly, and namely, to express their sympathy

with those devoted friends of humanity, the Rev.d Charles, T Toney, and Captain

Jonathan Walker, who are now incarcerated in the prisons of Mary Land [sic] and

West Florida, for having aided, or attempted to aid, some of their enslaved

countrymen in their escape from bondage; and to assure these christian

philanthropists, that they consider the cause for which they may here-

after be called to suffer, as honorable to them as men and as Christians;

and the laws under which they are to be arraigned, as utterly disgraceful

to a civilized community, and in the highest degree repugnant to the

spirit and precepts of the gospels.

On behalf of the Committee

October 8th 1844 – Thomas Clarkson

President.

John Scoble,

Secretary.

Capt Jonathan Walker

Listen: The Latin Program

Listen: The Latin Program